tesis_elisagironzetti

-

Upload

fran-cintado-fernandez -

Category

Documents

-

view

213 -

download

0

Transcript of tesis_elisagironzetti

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

1/760

UN ANLISIS

PRAGMTICO-EXPERIMENTAL DEL

HUMOR GRFICO. SUS APLICACIONES

AL AULA DE ELE

Elisa Gironzetti

http://www.eltallerdigital.com/http://www.ua.es/ -

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

2/760

Departament de FilologiaEspanyola, Lingstica General i Teoria de la Literatura

Departamento de Filologa Espaola, Lingstica General y Teora de la Literatura

UNANLISISPRAGMTICO-EXPERIMENTALDELHUMOR

GRFICO.

SUSAPLICACIONESALAULADEELE

TESISDOCTORAL

Presentada

por

Elisa

Gironzetti

DirigidaporDr.XoseA.PadillaGarca

Julio2013

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

3/760

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

4/760

UN ANLISIS PRAGMTICO-EXPERIMENTAL DELHUMOR GRFICO

SUS APLICACIONES AL AULA DEELE

TESIS DOCTORAL

PRESENTADA POR:Elisa Gironzetti

DIRIGIDA POR:Dr. Xose A. Padilla Garca

Alicante, 2013

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

5/760

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

6/760

Ai miei genitori

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

7/760

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

8/760

"Todo es un cuento, Martn. Loque creemos, los que conocemos,lo que recordamos e incluso lo

que soamos. Todo es un cuento,una narracin, una secuencia de

sucesos y personajes quecomunican un contenido

emocional. Un acto de fe es unacto de aceptacin, aceptacin

de una historia que se nos

cuenta. Slo aceptamos comoverdadero aquello que puede ser

narrado."

Carlos Ruiz Zafn

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

9/760

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

10/760

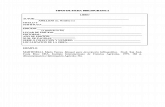

I

PRIMERA PARTE

OBJETO DE ESTUDIO Y ESTADO DE LA CUESTIN

: ................................................................... 1

1.1. I ............................................................................................................. 1

1.1.1. O ................................................................................................................ 2

1.1.2. H .............................................................................................................. 4

1.1.3. O .............................................................. ........................................... 9

1.1.3.1. E ................................................................................................ 9

1.1.4. C ...................................................................................................... 11

1.1.5. T .............................................................................................................. 14

1.2. I ........................................................................................................... 17

1.2.1. O ............................................................................................... 18

1.2.2. H ............................................................................................... 21

1.2.3. E ............................................................................................... 25

1.2.3.1. L .................................................................................... 25

1.2.3.2. L ............................................................................................... 28

1.2.4. E ............................................................. .................................................... 32

: ....................................................... 34

2.1. I ........................................................................................................... 34

2.2. T ....................................................................................................... 37

2.2.1. L .............................................................. 37

2.3. T .............................................................. .................... 46

2.3.1. L ...................................................................................... 46

2.3.2. E XVII ................................................... ............................... 47

2.3.3. E I ............................................................. 51

2.3.4. E XIX ....................................................... .......... 57

2.4. L : .............................. 60

2.4.1. L .......................................................................................... 61

2.4.2. L ............................................................ . 70

2.5. L ............................................................... 75

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

11/760

II

2.5.1. T ............................................................ .. 75

2.5.2. L R (1979, 1985) ................................ 84

2.5.2.1. E .................................................... ................................... 86

2.5.3. L A (1994, 1997)............................................................................... 90

2.5.4. L A R (1991)............................ 93

2.5.4.1. E GTVH ........................................... 96

2.5.5. E .......................... 100

2.5.6. E .............................................. 104

2.5.6.1. E GRIALE ...................................................... ........ 106

2.5.7. E ......................................... 112

2.5.8. E ............................................................ 118

2.5.8.1. , .............................................................................. 123

2.6. O ............................................................ 1282.6.1. L ................................................................................ 128

2.6.2. L ................................................................................... 130

2.6.3. L ............................................................................................... 135

2.6.3.1. L ............................................................ .................. 137

2.6.3.2. E EEG, ERP MEG .............................................. 139

2.6.3.3. E MRI .............................................................................. 143

2.7. C ........................................................................................................ 148

SEGUNDA PARTE

MARCO TERICO Y HERRAMIENTAS DE ANLISIS

: ..... 155

3.1. I ...................................................................................................... 155

3.2. E : ............................................... 157

3.3. H ........................................................... 162

3.3.1. E (G, 1975) ....................................................... ........ 162

3.3.2. L (A, 1962) ...................................................................... 163

3.3.3. E ........................................................................................ 165

3.3.3.1. P ................................................................................................. 166

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

12/760

III

3.3.3.2. I ....................................................................................................... 173

3.3.3.3. I .................................................... 174

3.3.3.3.1. L , ..................................... 178

3.3.3.3.2. L , ............................................... 180

3.3.3.3.3. L , ................................................ 183

3.3.3.4. I .............................................................................. 186

3.3.3.5. E (L, 2000) ....................................... 189

3.3.4. L (P G, 2012) ........................................... 191

3.3.5. L ................................................................................... 192

3.3.6. E .............................................................. ........ 196

3.3.6.1. E ................................................................................................... 198

3.3.7. E .......................................................... .................. 200

3.3.8. E .................... 2023.4. C ................................................... ................................................... 207

TERCERA PARTE

EL ANLISIS DEL CORPUS

EL PROCESO DE COMPRENSIN DE LAS VIETAS CMICAS

: ........................ 213

4.1. I ...................................................................................................... 213

4.2. L ............................................................... ............................. 214

4.2.1. L ............................. 214

4.2.2. D .................................................................. 216

4.2.2.1. E VC ........................................................................ 220

4.2.2.2. E VC ..................................................................... 224

4.2.3. L ............................................ 227

4.2.3.1. L ............... 228

4.2.3.1.1. L VC ........................................................................... 230

4.2.3.2. .................................................................. ....... 234

4.2.4. L ........................................................... 236

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

13/760

IV

4.2.4.1. L ............................................ 240

4.2.4.2. L .............................................. 242

4.3. C ................................................... ................................................... 246

:

................................................................................................................ 249

5.1. I ...................................................................................................... 249

5.2. L VC ......................... 251

5.3. D ........................................................ 256

5.4. E ...................................................... ................... 260

5.4.1. E ..................................................................... 260

5.4.2. L ...................................................................................................... 263

5.5. E ...................................................................... 267

5.5.1. L ......................................................... .................. 272

5.5.2. L .......................................................... .................. 276

5.5.2.1. T ....................................................... ........ 281

5.5.3. L ..................................................................... 286

5.5.3.1. I ........................................................................ 286

5.5.3.2. L ICP ................................................................................. 288

5.6. E : ........................................................... 293

5.6.1. C , .............................. 301

5.6.2. C ........................................ 304

5.7. C ................................................... ................................................... 307

:

................................................................. 310

6.1. I ...................................................................................................... 310

6.2. E ........................................................................................... 311

6.3. E ........................................................................................ 315

6.3.1. M .............................................................................................................. 316

6.3.1.1. P ...................................................................................................... 316

6.3.1.2. D ............................................................................................ 319

6.3.2. R ......................................................................................................... 321

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

14/760

V

6.4. E ................................................................................ 325

6.4.1. M .............................................................................................................. 325

6.4.1.1. P ...................................................................................................... 325

6.4.1.2. D ............................................................................................ 328

6.4.2. R ......................................................................................................... 330

6.4.3. C ................................................... ................................................... 337

6.5. E .................................................................................... 340

6.5.1. M .............................................................................................................. 342

6.5.1.1. P ...................................................................................................... 342

6.5.1.2. D ............................................................................................ 345

6.5.2. R ......................................................................................................... 349

6.5.3. C ................................................... ................................................... 358

CUARTA PARTE

APLICACIONES PRCTICAS DE LOS RESULTADOS DEL ANLISIS

A LA CLASE DE E/LE

:

................................................................................................................ 369

7.1. I: .......................................................... 369

7.2. H (E)LE ................................................................................. 371

7.3. U () (E)LE ................................ 375

7.3.1. E , PCIC MCER ................................................................................. 378

7.3.2. D .................................................................... 382

7.3.3. C ....................................................................................... 386

7.4. L : ........................................... 388

7.4.1. J .......................................................... .................. 388

7.4.2. F .......................................................................................... 390

7.4.3. G ........................................................................................... 392

7.4.4. M ..................................................................................... 394

7.4.5. S ............................................................................................................ 402

7.5. L : ..................................................... 405

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

15/760

VI

7.5.1. J .......................................................... .................. 405

7.5.2. F .......................................................................................... 406

7.5.3. G ........................................................................................... 413

7.5.4. M ..................................................................................... 414

7.5.5. S ............................................................................................................ 425

7.6. L : ............................................... 427

7.6.1. J .......................................................... .................. 427

7.6.2. F .......................................................................................... 429

7.6.3. G ........................................................................................... 432

7.6.4. M ..................................................................................... 433

7.6.5. S ............................................................................................................ 439

7.7. L : .......................................... 442

7.7.1. J .......................................................... .................. 4427.7.2. F .......................................................................................... 444

7.7.3. G ........................................................................................... 446

7.7.4. M ..................................................................................... 448

7.7.5. S ............................................................................................................ 454

7.8. L : ................................................. 455

7.8.1. J .......................................................... .................. 455

7.8.2. F .......................................................................................... 457

7.8.3. G ........................................................................................... 4597.8.4. M ..................................................................................... 460

7.8.5. S ............................................................................................................ 467

7.9. C ........................................................................................................ 470

QUINTA PARTE

CONCLUSIONES

: ..................................................................... 477

8.1. L ......................................................................................................... 477

8.1.1. P VC ........................................ 478

8.1.2. L VC (E)LE .......................................................................... 488

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

16/760

VII

8.1.3. P ............................................................... .................. 490

8.2. T ............................................................................................................ 493

8.2.1. P ......................... 494

8.2.2. C S FL .............................................................. 503

8.2.3. P .......................................................... ............................. 505

BIBLIOGRAFA

...........................................................................................................

APNDICES

: ..................................................................

: ..............................................................

: ..................................................................

: ....................................................

: ...........................................

1. L ............................................................ ...............................

1.1 V E R ................................................................................. .............

1.2 V E ....................................................... .........................................

1.3 V F ................................................... .......................................

1.4 V F ..................................................... .......................................

1.5 V M F .......................................................... ................

1.6 V M................................................................................................

1.7 V N ...............................................................................................

1.8 V P ..................................................... ...................................... 1.9 V R .......................................................................................... .....

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

17/760

VIII

1.10 V R ..................................................... ..........................................

1.11 V ...................................................... .............................

2. L ...................................... ......................................................

2.1 V B...................................................................................................

2.2 V F ............................................................. ...............................

2.3 V G ........................................................ ...........................................

2.4 V G ...........................................................................................

2.5 V H ................................................................................................

2.6 V K .................................................... ........................................

2.7 V L ............................................................. ............................

2.8 V M ............................................................. ............................

2.9 V M ......................................................................................

2.10 V M ................................................................................................. 2.11 V M .........................................................................................

2.12 V O ..................................................... .........................................

2.13 V P ............................................................................................

2.14 V P ...................................................... ........................................

2.15 V R ............................................................. ...........................

2.16 V SDRU ..............................................................................................

2.17 V S .................................................................................. ...........

2.18 V T ......................................................... ....................................... 2.19 V V ....................................................... .......................................

2.20 V ...................................................... .............................

: ............................................

1. E ........................................................ .........................................

1.1 P ......................................................................................................... 1.2 D ....................................................................................................................

2. P ...............................................................................................

2.1 P ..................................................... ....................................................

2.2 D .......................................................................................................................

3. S ( ) ................................................. .......

3.1 P ................................................................. ......................................

3.2 D ........................................................ ............................................................ .

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

18/760

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

19/760

i

Agradecimientos

Esta tesis doctoral es el resultado de varios aos de investigacin y

reflexin sobre el tema de las vietas cmicas desde una perspectivamultilinge e interdisciplinar que abarca la pragmtica, la

psicolingstica y la didctica de lenguas extranjeras. Las personas que

han colaborado en la realizacin de este trabajo han sido muchas, y

quiero dar las gracias a cada una de ellas por haber aportado su granito

de arena. En particular, agradezco mucho la paciencia y la

disponibilidad de todas aquellas personas que aceptaron participar como

voluntarios en los experimentos psicolingsticos de Bristol, Miln y

Alicante, y a mis alumnos de espaol para extranjeros de las

univerisdades de Bristol y Bath, ya que sin su colaboracin este trabajo

no se hubiera podido llevar a cabo.

En primer lugar, quiero dar las gracias a mi director de tesis, el Dr.

Xose A. Padilla Garca, por haberme animado a llevar a cabo mis

primeras investigaciones y presentaciones a congresos cuando todavaera una alumna del Mster de Espaol e Ingls como LE/SL, y por

haberme motivado y aconsejado a lo largo de todos estos aos. Su apoyo

ha sido decisivo y me ha permitido crecer tanto personal como

profesionalmente.

En segundo lugar, quiero agradecer al Dr. Markus Damian, del

departamento de Psicologa Experimental de la Universidad de Bristol,

por su paciencia y su ayuda, en particular en relacin con la parte

experimental de esta investigacin.

Quiero dar las gracias tambin al Dr. Salvatore Attardo, por las

interesantes conversaciones mantenidas acerca del tema del humor

grfico y el papel de la caricatura en el proceso de comprensin de las

vietas cmicas.

Finalmente, quiero agradecer a mi familia y a mis amigos por su

cario y su apoyo incondicionado, sin los cuales nunca hubiera podido

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

20/760

ii

plantearme alcanzar esta meta profesional. Sobre todo, les doy las

gracias a mis padres por haber despertado en m la pasin por las

lenguas extranjeras cuando era slo una nia, llevndome de viaje por

Europa, y por haberme enseado a tomarme la vida con humor. Unagradecimiento especial a Alberto, que crey en m desde el principio y

estuvo siempre a mi lado durante el desarrollo de esta tesis, y a Irene,

que me soport, me ayud y hasta me acogi en su casa cuando lo

necesit.

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

21/760

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

22/760

PRIMERA PARTE

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

23/760

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

24/760

OBJETO DE ESTUDIO Y ESTADO DE LACUESTIN

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

25/760

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

26/760

"Man is the only animalthat laughs and weeps;

for he is the only animalthat is struck with the

difference between whatthings are, and what

they ought to be.

William Hazlitt

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

27/760

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

28/760

1

Captulo I: CONCEPTOS PREVIOS

1.1. Introduction

When the expression and the comprehension of a foreign language

are concerned, humor, in all its variants and without any doubt,

represents an obstacle that many people (teachers, students, and even

native speakers) will consider very difficult to overcome. My personal

experience as a learner of Spanish, English, and French could serve as

an example. I clearly remember the frustration that I felt when myfriends, all native speakers of those languages I was learning, used to

joke and laugh at something, while I, despite having a good

understanding of the language, was only able to say, I dont get it.

The truth is that knowing the language used by the humorist is not

enough to appreciate and enjoy the humorous effect. However, the

language does play a fundamental role, since it is the key that gives

access to the humorous text in the first place.

Each time someone smiles or laughs because a joke has been told or

because of the funny cartoon published in the newspaper, he or she does

not rely solely on his or her linguistic knowledge. In fact, the process of

understanding and appreciating humor involves the reader/hearers

previous knowledge about the world, and, above all, the activation of

some specific cognitive processes that finally lead us to perceive thepleasure commonly associated with humor.

The case of the cartoons mentioned above is precisely what

interested me the most because, when I was a student of Spanish as a

Foreign Language, it was often impossible to understand those texts and

images that many Spanish native speakers read and enjoyed on a daily

basis, apparently without any effort.

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

29/760

2

What happens in our minds in order for us to be able to enjoy the

humorous effect that certain texts produce? What makes a cartoon funny

for some, and meaningless or even of bad taste for others? These were

some of the questions that led me to start this research project, which ischaracterized by having a pragmatic and experimental orientation, and a

practical application to the field of teaching Spanish as a Foreign

Language.

1.1.1. Objectives

The main objective of this work was to analyze the pragmatic and

communicative mechanisms underlying the communication between the

humorist, or creator of the comic cartoon, and the reader of the same

cartoon.

To accomplish this goal, this research has been structured in a series

of subsequent steps, which simultaneously represent the different

sections of the dissertation. These steps consist of:

- Analyze and describe the humorous communication in general.

- Analyze and describe the humor in comic cartoons.

- Describe, from a pragmatic perspective, the communication between

the humorist and the reader of the comic cartoon.

Following these goals, the first research question that this work will

try to answer is the following: what are the elements that contribute to

humorous communication?

In order to answer this question, an extensive literature review of the

different theories and approaches is presented. This review will cover

the main studies on humor, from the classics, such as Plato and Aristotle,

until the modern theories of Attardo and Raskin.

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

30/760

3

Moreover, the state of the art will also include the review of some

interesting contributions from psycholinguistics and neurolinguistics, as

these combine the theoretical approach of linguistics with a scientific

experimental methodology. In fact, these new contributions allowed fora rapid progress of humor studies during the last years, and many

theoretical proposals found their confirmation in the data thus obtained.

The second research question that motivates and structures this

dissertation is the following: how is the humorous effect produced in

comic cartoons?

In order to answer this question, the analysis of a bilingual Spanish-

Italian corpus of comic cartoons has been undertaken. The aim of this

analysis is to describe the humorous mechanisms and the characteristics

of different types of humor in comic cartoons. The textual analysis of

comic cartoons will be paired with a detailed description of the type of

text they belong to. Following this approach, before starting to answer

the third research question, the reader will have been offered a precise

description of the object of study, that is to say, comic cartoons.

Finally, the third research question that this work aims at answering

is: how do the humorist and the reader communicate through comic

cartoons?

In order to answer this question, a pragmatic perspective of analysis,

based on Grice (1975) and Levinson (2000), has been combined with a

cognitive approach based on the schema theory of Rumelhart (1975),

Shank (1975), and Abelson (1975). The comic cartoons of the corpuswill be analyzed according to this theoretical framework, paying special

attention to the type of implicit contents and the role of the pragmatic

communicative principles. The pragmatic and textual analysis will be

complemented by an experimental study based on the theory of semantic

priming, and on the study of the reaction time of a subject in relation to a

given stimulus. The aim of these studies will be to contribute some

experimental data to confirm or dismiss the theoretical proposals.

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

31/760

4

Besides the main objective, which is structured in the three sub-

objectives already described, this work also has a second main goal,

which is different from the first both theoretically and methodologically.

This second objective consists of the following:- Analyze the problems that Spanish as a Foreign Language students

could have when faced with the comprehension of Spanish comic

cartoons, and create some learning materials that will teach them how to

overcome these obstacles.

In order to accomplish this goal, the results of the pragmatic analysis

of comic cartoons will be applied to the specific context of an

undergraduate course of Spanish FL at the University of Bristol in

England.

The knowledge of the specific teaching and learning context will

permit the recognition of some of the obstacles that students will have to

overcome and the linguistic and non-linguistic knowledge students will

need in order to understand comic cartoons in a real communicative

situation outside the classroom. According to the study a complete

lesson plan will be created with the aim of teaching these students how

to read, understand, and learn from Spanish comic cartoons. The

theoretical framework of this last section of the dissertation follows the

directories of the Common European Framework of Reference for

languages (CEFR) and the Cervantes Institute Curricular Plan (CICP).

1.1.2. Hypotheses

Based on the study of previous research, it has been possible to

formulate some hypotheses that, parallel to the objectives mentioned in

the preceding section, structure the present work and guide the reader

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

32/760

5

through it. These hypotheses encompass different aspects that will be

touched upon throughout this work, which are:

1) The narrative and textual structure of comic cartoons and how

they work from a cognitive perspective.2) The existence of different levels of comprehension of comic

cartoons.

3) Communication through comic cartoons.

The first hypothesis, concerning the narrative and textual structure of

comic cartoons and its cognitive operation, is based on the internal and

external clues theory (Padilla, 2004; Padilla and Gironzetti, 2012a), the

schema theory (Rumelhart, 1975; Shank, 1975), and the Marked

Informativeness Requirement proposal (Giora, 1991).

The concept of clue has been applied to the study of humorous texts

by Padilla and Gironzetti (2009). According to this proposal, there are

two different types of clues: a) contextualizing reading clues, or external

clues, which frame the text and guide the reader through its

interpretation and comprehension; and b) content clues, or internal clues,

which refer to the themes and contents of the text.

The concept of scripts or schemata comes from Rumelhart (1975)

and Shank (1975). Rumelhart, on one hand, argues that speakers have

some mental scripts containing information about the structure of texts

and use them to generate expectations and anticipate how the narration

will unfold. Shank, on the other hand, defines a script as a casual chainthat provides information about the world in relation to very frequent

situations. In other words, a script is a sequence of predetermined

actions or events that define a situation.

Finally, Giora (1991) proposes the existence of a Gradual

Informativeness Principle, according to which all narrative texts

gradually progress from less to more informativeness. This principle,

however, is marked in the case of jokes (Marked Informativeness

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

33/760

6

Requirement), that is to say, jokes progress from less to more

informativeness suddenly rather than gradually.

Based on these three proposals, the first hypothesis is that comic

cartoons represent a specific type of text within the humorous genre, andas such are characterized by:

- The presence of specific external clues. The body of external clues will

constitute, on a cognitive level, a formal script or schema associated

with the type of text of comic cartoons.

- The presence of specific internal clues, which will activate relevant

content scripts on the cognitive level. The activation of these scripts will

allow for a humorous incongruity to occur.

- A marked informative structure, in the respect of the Marked

Informativeness Requirement of Giora (1991), which will affect how the

conversational principles of Levinson (2000) operate.

The second hypothesis at the basis of this dissertation concerns the

existence of different levels of comprehension of comic cartoons and is

based on the aforementioned script theory (Shank, 1975; Rumelhart,

1975), the Semantic Theory of Verbal Humor (henceforth STVH) of

Raskin (1979, 1985), and Attardos proposal (1994, 1997), which, in

turn, is based on other previous theories such as Greimas (1966), Morin

(1966, 1970), and Suls (1972).

The STVH by Raskin (1979, 1985) establishes the necessary

conditions for a text to be considered humorous, and these are: a) thetext has to be compatible, at least in part, with two different frames or

scripts, and b) these two frames or scripts have to be overlapping and in

opposition.

Attardo (1994, 1997) develops a theory known as SIR, which stands

for Set-up, Incongruity, Resolution, the three phases of which a joke is

made, according to Attardo. The initial introductory phase, the set-up, is

followed by a central phase in which the incongruity occurs, and a final

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

34/760

7

phase in which the reader/hearer is able to solve the incongruity and re-

establish the lost balance.

Therefore, the second hypothesis postulates the existence of different

levels of comprehension of comic cartoons according to the multimodalstructure of this type of texts. These levels will be related to the

activation of different scripts and cognitive processes and will determine

the level of understanding and enjoyment of the reader.

From this second hypothesis derives another hypothesis, which is at

the origin of the development of the experimental study of comic

cartoons. More specifically, supposing that these different levels of

comprehension exist and are structured from less to greater complexity,

and knowing that a higher cognitive complexity requires a longer

execution time1, it is possible to postulate that readers will need more

time to access the deepest levels of comprehension of comic cartoons.

Finally, the third and last hypothesis concerns the communication

that occurs through comic cartoons. This hypothesis is based on the

works of Zhao (1988) and Attardo (1994, 1997) on the types of

messages conveyed by and through jokes and the pragmatic theories of

Lewis (1979) and Levinson (2000).

Zhao (1988) (and later, Attardo2), stated that jokes, despite being a

non bona-fide (NBF) type of texts and violating the Gricean cooperative

principle, can convey bona-fide (BF) information, true and cooperative

contents.

Levinson (2000) revised Grices proposal (1975) and substituted theconcept of maxim with the idea of communicative principle, further

developing the concepts of generalized and particularized conversational

implicature. According to Levinson (2000) a generalized conversational

implicature (henceforth GCI) is a type of implicit content inferred by

default, automatically, on the basis of some conversational principles.

1See Fodor (1983).

2See Attardo (1994, 1997).

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

35/760

8

On the other hand, a particularized conversational implicature

(henceforth PCI) can only be inferred in a specific context.

Finally, Lewis (1979) was concerned with the role of presuppositions

(Stalnaker, 1970; Karttunen, 1973a and 1973b; Heim, 1992) incommunication, and demonstrated that it is almost impossible to say

something that is unacceptable due to the lack of presuppositions.

According to Lewis, at the very moment of saying something that

requires the existence of a certain presupposition that has not been

established before, this same presupposition will start to exist. This

process has been called by Lewis accommodation.

Based on these proposals, the third hypothesis of this research

postulates that comic cartoons can communicate simultaneoulsy NBF

and BF contents, and these different contents are linked to different

inferential paths occurring at different stages of the comprehension

process of comic cartoons.

From this third hypothesis derives another hypothesis, linked to the

experimental section of this dissertation, especially with the semantic

priming experiments (see McNamara, 2012). In this case, if it is true that

comic cartoons can convey BF information, this will be reflected in the

results of semantic priming experiments. The methodology of these

experiments will be detailed in Chapter VI.

This third hypothesis and its corresponding sub-hypothesis are also

related with the second general objective of this research, namely, the

creation of teaching and learning materials for Spanish FL students. Inparticular, if comic cartoons can convey BF information (Zhao, 1988),

then, as will be shown in Chapter VII, students can also learn BF

contents from these texts.

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

36/760

9

1.1.3. Object of study

1.1.3.1. Etymology of humor3

After having explained what the goals of this dissertation are, this

section will be used to define the object of study, that is to say, comic

cartoons, a specific type of humorous text. This section will start by

exploring the origins and meaning of the current term humor and will

then move on to describe the characteristics and components of comic

cartoons.

According to the Real Academia de la Lengua Espaola, the

meaning of the term humor, which comes from Latin humor, is the

following: 1. m. Genio, ndole, condicin, especialmente cuando se

manifiesta exteriormente. 2. m. Jovialidad, agudeza. Hombre de humor.

3. m. Disposicin en que alguien se halla para hacer algo. 4. m. Buena

disposicin para hacer algo. Qu humor tiene! 5. m. humorismo (modo

de presentar la realidad). 6. m. Antiguamente, cada uno de los lquidosde un organismo vivo. 7. m. Psicol. Estado afectivo que se mantiene por

algn tiempo..

By observing the sixth entry reproduced above it can be seen that in

the past the word humorwas used with a very different meaning from

the one it has today. In fact, the word humoresreferred to the different

liquids or fluids of the human body, which included blood, bile, and

phlegm. A Greek medical precursor, Galeno (130 - 200 A. D.), attributed

to the excess of certain corporal fluids some psychological

characteristics, stating that the different humoresof the human body and

their fluctuations were responsible for changes in peoples states of

mind.

3See Wickberg (1998) and Martin (2007) for a complete history of the concept and meaningof humor.

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

37/760

10

Starting with Galenos hypothesis, the term humorbegan to acquire

psychological and negative characteristics. However, until the XVI

century, the word humor had never been used to refer to someone

laughed at by others because of his or her eccentric personality orbehavior. In fact, the XVI century was a decisive era in the evolution of

the meaning of humor, since before then there was no relation between

humorand the idea of ridicule.

During the XVIII century, the word ridiculehad been used to refer to

what was capable of generating an aggressive and humiliating laughter,

according to the theory of Aristotle, who considered laughter as

something negative. In spite of being negatively marked, laughter was

socially accepted as a form of entertainment for the highest social

classes. For this reason, Wickberg (1998) believes that it is possible that

during that period, and due to its large social acceptation, laughter

started to have a positive connotation. Step by step, and very slowly, the

intellectual component of laughter became more important than the

pejorative and humiliating one.

Based on this new meaning of humor, coined in the XVI century,

people started using also the words humorist to refer to the target of

humor and man of humor to refer to the person who had the gift of

making people laugh. This distinction lasted until the XIX century when

the word humoriststarted to be used with its modern meaning to refer to

the person who makes people laugh, and the expression man of humor

dies out.It was also in the XIX century when the last change in the meaning

of humorhappened. This change caused the English word humor to be

used with the meaning it has nowadays. As a consequence of the use of

the word wit, used to refer to a kind of humor that produced an

aggressive, sarcastic and intellectual laughter, the meaning of humor

became even more specific, until it came to be used only to refer to the

kind of humor that produced a benevolent laughter.

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

38/760

11

The word humor, its use and meaning have undergone many changes

and phases, evolving and specializing during the centuries. However, as

the excerpt from the dictionary of the Real Academia de la Lengua

Espaolademonstrates, the word humoris still used with many differentmeanings. The truth is that the very nature of humor is still a mystery.

Despite the efforts of many scholars who devoted their professional lives

to it and whose works will be reviewed in the chapter devoted to the

state of the art, it is still impossible to clearly answer the question what

is humor? However, thanks to those same scholars, it is possible to

currently define certain elements that produce humor and some of the

texts people used to convey or communicate with humor.

1.1.4. Comic cartoons

Within the framework of visual humor, a comic cartoon has been

considered the equivalent of what jokes are for verbal humor. This

means that comic cartoons are a prototypical example of visual humor

(Paolillo, 1998; Coulson and Kutas, 2001; Hemplemann and Samson,

2008). Comic cartoons are a type of text which belongs to the humorous

genre, made up by a written text and a comic image 4, which often

includes a caricature (Padilla and Gironzetti, 2012a). Depending on the

style and intentions of the author, each element can have the gestaltic

role of figure or background or, in other words, can be the primary or

secondary source in the transmission of the general meaning of the text5.

4 It is also true that there are certain comic cartoons that do not have a textual component.However, for the purposes of this study, only those comic cartoons with both components have

been studied.

5 The concepts of figure, or foreground, and ground, or background, come from Gestaltpsychology, a branch of cognitive psychology that studies perception.This distinctiondifferentiated between those elements that a person (reader or hearer) sees as relevant (thefigure), and those that are perceived as being secondary (the ground). This dichotomy has

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

39/760

Specifically, e

humorous eff

place in the

2007).

Example 1. Thcartoons

The previo

and image ar

the text. In t

humorous inc

and CardinalBesides h

also include t

sociocultural

belonging to

important conseqinformation. See a

6Cardinal Antoniexample 1 was pu

ach of the two components can contribu

ct, or the humorous incongruity (Suls

ritten text, in the image, or in both (Sa

iconic component and the textual comp

us example reproduces a comic cartoon i

equally important in order to understan

is example, both components contrib

ongruity between two worlds, in this c

Rouco6

.aving a textual and an iconic componen

he presence of a third and fundamenta

omponent. This component refers to a

a specific culture and used by na

ences for the study of how we comprehend, rlso Chvany (1985).

Mara Rouco Varelabecame well known, just beforlished, for his firm opposition to the right of women

12

e to generate the

1972) can take

son and Huber,

nent in comic

n which both text

d the meaning of

te to generate a

se, Coca-Cola

, comic cartoons

component: the

l those elements

ive speakers to

member and process

e the comic cartoon ino abort.

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

40/760

contextualize

traditions, edu

in Example 2,

tradition, in Sshoes by the

Example 2. Th

The com

magazines, an

to any current

comic cartoo

cartoons, are

on some curunderstand th

The follo

a comic carto

7The expression ano reference to thexpression is notBequer, for exam

between the comic

a given situation. These include

cative models, etc. In order to interpret t

for instance, it is necessary to know tha

ain, on the night of the 5th

of January, cindow so that the Magi can fill them wit

sociocultural component in comic carto

c cartoons are usually published in

d more recently also online. Some of th

event and are an example of what has b

ns7, while others, that have beenna

articularly interesting because they refe

ent events that the reader needs to kmessage.

ing graph summarizes the main characte

n and differentiate between its subtypes.

bsurd comic cartoonis here used to refer to those coe sociocultural reality contemporary to their creatiorelated to the classic use of the term absurd hum

ple), but instead, in this context, simply refers tocartoon and reality.

13

eligious beliefs,

he comic cartoon

according to the

ildren leave theirpresents.

ns

newspapers and

m are not linked

en called absurd

edcritical comic

to and comment

now in order to

ristics that define

ic cartoons that maken or publication. Thisor (see the works ofa lack of relationship

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

41/760

14

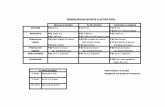

Graph 1. Absurd and critical comic cartoons

According to this schema, an absurd or critical comic cartoon is a

type of humorous text belonging to the realm of fiction and

characterized by the presence of three components: iconic, textual, andsociocultural. Moreover, critical comic cartoons add a forth component:

a reference to some event or person of the current sociocultural reality.

1.1.5. The corpus

The corpus that has been used for the present research comprises 600

Italian and Spanish comic cartoons, published between 2006 and 2012

and later classified as criticalandabsurd comic cartoons. After having

completed the pragmatic analysis of the comic cartoonsand having

verified that the examples counted with the same range of

characteristics, a collection of 161 samples has been selected as

representative of the whole corpus (see Appendix V). This selection of

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

42/760

15

samples has then been used to complete more specific studies, such as

the development and realization of the psycholinguistic experiments (see

Chapter VI) and the planning of the pedagogical application (see

Chapter VII). Of these 161 samples, 90 are Spanish comic cartoons and71 are Italian comic cartoons.

Graph 2. Bilingual sub-corpus of comic cartoons

The comic cartoons that constitute both the general corpus and the

sub-corpus have been chosen on the basis of the following criteria: a)

variety of publications and authors; b) variety of themes and topics; c)

for the sub-corpus, belonging to one of the two subgroups (absurd and

critical).

As far as the variety of publications and authors is concerned, this is

a fundamental criterion because each author has his or her own style and

every publication has a clear political or ideological affiliation.Both are

reflected in the comic cartoon, therefore, in order to guarantee that the

samples included in the sub-corpus were representative; the sub-corpus

consists of comic cartoons by 37 Italian authors and 26 Spanish

authors.Furthermore, all the examples have been obtained from a total of

30 different publications for the Italian cartoons, and 16 different

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

43/760

16

publications for the Spanish cartoons. These publications included

newspapers, magazines, books and web pages.

In relation to the themes and topics of the cartoons, the corpus

includes cartoons referring to both national and international topics.This criterion is relevant because it allows for a comparison of themes

and topics across cultures. This is especially relevant for the pragmatic

analysis, but also for the pedagogical application, since one can observe

the differences in the way the same topic is framed within one culture or

the other. The analysis of this aspect will show the differences in topic

choice and humorous narrative between Spanish and Italian humor.

Finally, concerning the aforementioned classification of cartoons

into critical and absurd types, this is necessary in order to explore the

activation of different cognitive processes and explain how the different

types of comic cartoons differ on the cognitive and textual levels.

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

44/760

17

1.2. Introduccin

La comprensin del humor constituye sin duda un obstculo que

muchos, profesores, aprendices e incluso hablantes nativos de la lenguacalificaran, en ocasiones, como insuperable.

Mi experiencia personal como aprendiz de espaol, ingls y francs

como lengua extranjera podra ser un ejemplo. Recuerdo perfectamente

la frustracin que senta cuando mis amigos extranjeros bromeaban o se

rean de algo, mientras yo, a pesar de tener un buen nivel de

conocimiento del idioma, me preguntaba por qu mi nica respuesta

ante esas bromas era siempre no lo pillo.

El caso es que para comprender y disfrutar del efecto humorstico no

es suficiente conocer el idioma en el que se comunica el humorista,

aunque es cierto que ste tiene un papel fundamental, ya que constituye

la clave que da acceso al texto humorstico en s. Cada vez que alguien

sonre, o sere, porque acaba de escuchar un chiste, o porque la vieta

publicada en el peridico le ha hecho gracia, no recurreslo a susconocimientos lingsticos. De hecho, en este proceso de comprensin

entran en juego tambin los conocimientos previos acerca del mundo y,

sobre todo, se ponen en marcha toda una serie de procesos cognitivos

que tienen como resultado final esa sensacin tan placentera que se

asocia con el humor.

Justamente el caso de las vietas cmicasantes citado fue lo que ms

llam mi atencin, ya que para m, estudiante extranjera de espaol, aveces era casi imposible entender esos textos e imgenes que miles de

espaoles lean y disfrutaban a diario, aparentemente sin ningn

esfuerzo. Qu es lo que ocurre en la mente para que sea posible

disfrutar del efecto humorstico que determinados textos producen?

Qu es lo que hace que una vieta cmica sea graciosa para algunos, y

sin sentido, o incluso de mal gusto, para otros? Estas fueron las

preguntas que me empujaron a empezar la presente investigacin, quese

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

45/760

18

caracteriza por tener una orientacin pragmtica y experimental, y una

aplicacin prctica en el campo de la enseanza de espaol para

extranjeros.

1.2.1. Objetivos de la tesis

El objetivo principal de este trabajo es analizar los mecanismos

pragmtico-comunicativos que subyacen a la comunicacin que se

establece entre el humorista o creador de la vieta cmica (en adelante

VC8) y el lector de la misma.

Con el fin de alcanzar este objetivo hemos marcado una serie de

pasos, o subobjetivos, que a su vez constituyen las fases en las que se ha

estructurado la investigacin. Estos subobjetivos son los siguientes:

- analizar y describir la comunicacin humorstica en general;

- analizar y describir el humor en las VC;

- describir desde una perspectiva pragmtica la comunicacinhumorista-lector que se produce en las VC.

Los tres subobjetivos han sido planteados en forma de preguntasa las

cuales hemos intentado dar respuesta. La primera pregunta, que se

corresponde con el primer subobjetivo, es la siguiente: en qu consiste

la comunicacin humorstica?

Para intentar contestar a esta pregunta, presentaremos una exhaustiva

resea de la bibliografa sobre el tema desde diferentes perspectivas

tericas. La resea cubrir los principales estudios y teoras sobre el

humor, desde la edad clsica de Platn y Aristteles, hasta la poca

moderna de Attardo y Raskin. Adems, dedicaremos un espacio tambin

8 Para una mayor claridad, se ha incluido al final del presente trabajo una Tabla deabreviaciones (vase el cuarto apndice), en la que se proporciona una breve descripcin delsignificado de cada abreviacin y sigla utilizada. Las abreviaciones se han incluido en ordenalfabtico.

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

46/760

19

a las contribuciones que provienen de disciplinas afinesa la lingstica

como la psicolingstica y la neurolingstica, que tienen el mrito de

combinar las propuestas tericas lingsticas con una metodologa

investigadora cientfica y experimental. Estos nuevos enfoqueshanpermitido que en los ltimos aos los estudios sobre el humor

avanzaran rpidamente, y muchas de las propuestas tericas encontraran

fundamento y confirmacin gracias a la aportacin de los nuevos datos

cientficos.

La segunda pregunta a la que se quiere dar respuesta con este trabajo

es: cmo se produce el humor en las VC?

Para contestar a esta pregunta, llevaremos a cabo el anlisis de un

corpus bilinge espaol-italiano de vietas cmicas, con el fin de

describir los mecanismos humorsticos de las VC y establecer cules son

las caractersticas propias de losdiferentes tipos de humor en las VC.

Adems, el anlisis textual de las VC se enmarcar en una descripcin

detallada del tipo textual al que pertenecen.

De ese modo, antes de empezar a contestar a la tercera pregunta,

habremos ofrecido al lector una visin global de los estudios sobre

humor que se han llevado a cabo anteriormente, y una descripcin

detallada del objeto de estudio de este trabajo, es decir, las VC.

Finalmente, la tercera pregunta a la que se quiere encontrar respuesta

es la siguiente: cmo se comunican el humorista y su lector a travs

de las VC?

Para responder a esta pregunta, adoptaremos una perspectiva deanlisis pragmtico, basada en las propuestas de Grice (1975) y

Levinson (2000), y cognitivista, basada en la teora de los esquemas de

Rumelhart (1975), Shank (1975) y Abelson (1975). A partir de ah, se

analizarn las VC que componen el corpus,prestando atencin al tipo de

contenidos comunicados, en particular el contenido implcito, y a cmo

se sortean los principios comunicativos pragmticos en la comunicacin

entre humorista y lector que ocurre a travs de las VC. El anlisis

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

47/760

20

pragmtico-textual se complementar finalmente con unos estudios de

tipo experimental basados en la teora del primado semntico9 y en el

estudio de los tiempos de reaccin ante un estmulo dado, con el fin de

aportar datos experimentales capaces de confirmar o desmentir lapropuesta terica.

Adems del objetivo principal, cuyos tres subobjetivos se acaban de

describir, y que se enmarca en un estudio pragmtico de la

comunicacin, este trabajo tiene tambin un segundo objetivo, terica y

metodolgicamente separado del principal. Este objetivo es el siguiente:

- Analizar los problemas que un estudiante de espaol lengua

extranjera (en adelante, ELE) podra tener al enfrentarse con la

lectura y comprensin de las VC, y proporcionarle las herramientas

para facilitar la resolucin de estos problemas.

Para llevar a cabo este objetivo, aplicaremos los resultados obtenidos

del anlisis pragmtico de la comunicacin de las VC al contexto

especfico de la enseanza de (E)LE a estudiantes universitarios de la

Universidad de Bristol, en Inglaterra. El conocimiento del contexto

especifico de enseanza permitir establecer de manera clara y precisa

cules sern los obstculos que los estudiantes tendran que superar para

comprender las VC en un contexto real, fuera del aula de (E)LE, y de

qu recursos (lingsticos y no lingsticos) disponen pare enfrentarse a

ello. De acuerdo con este anlisis del contexto de enseanza y los

resultados del estudio pragmtico de las VC, crearemos una unidaddidctica con el fin de ensear a los alumnos de (E)LE a leer y

comprender una VC, con todos los pasos que esto conlleva. El marco

terico didctico adoptado para esta ltima parte seguirlas directrices y

los principios del Marco Comn Europeo de Referencia para las lenguas

9El primado semntico, como veremos ms adelante, es un efecto por el cual la exposicin deun sujeto a un determinado estmulo verbal influye en la respuesta que el mismo sujeto darante un estmulo presentado con posterioridad, debido a que los dos comparten ciertascaractersticas semnticas.

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

48/760

21

(en adelante, MCER) y del Plan Curricular del Instituto Cervantes (en

adelante, PCIC).

1.2.2. Hiptesis de partida

A partir del estudio de las investigaciones llevadas a cabo hasta la

fecha, ha sido posible avanzar unas hiptesis de partida que, de acuerdo

y en paralelo con los objetivos de la investigacin, estructuran este

trabajo y guan al lector por su recorrido, empezando por el estudio delhumor en la VC, hasta llegar a sus posibles aplicaciones prcticas en el

mbito de la didctica de las lenguas extranjeras.

Estas hiptesis abarcan diferentes aspectos que se tratarn a lo largo

de este trabajo, a saber:

1) La estructura narrativa y textual de las VC y su funcionamiento

desde una perspectiva cognitiva.

2) La existencia de diferentes niveles de lectura de las VC.

3) La comunicacin a travs de las VC.

La primera hiptesis, relativa a la estructura narrativa y textual de las

VCy su funcionamiento en el nivel cognitivo, se basa en la teora de los

ndices internos y externos del humor (Padilla, 2004; Padilla y

Gironzetti, 2012a), la teora de los esquemas de Rumelhart (1975)y

Shank (1975), y la propuesta de un requisito de informatividad marcada

(Giora, 1991).

El concepto de ndice fue aplicado al estudio de los textos

humorsticos por Padilla y Gironzetti (2009). Segn esta propuesta,

existen dos tipologas de ndices: a) ndices de contextualizacin lectora,

o externos, es decir, unas pistas interpretativas que enmarcan el texto

con el objetivo de guiar los procesos interpretativos de comprensin

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

49/760

22

dellector, y b) ndices de contenido, o internos, que hacen referencia a

los temas o contenidos del texto.

Por otro lado, el concepto de script (guin) se debe al trabajo de

Rumelhart (1975) y Shank (1975). Rumelhart afirmaba que los hablantesposeen unosscriptsmentales con informacin acerca de la estructura de

los textos, a partir de los cuales generan expectativas y pueden anticipar

cmo se desarrollar la narracin.Por su parte, Shank defini uno script

como una cadena casual que proporciona informacin acerca del mundo,

relacionada con situaciones muy frecuentes. En otras palabras, se trata

de secuencias de acciones o hechos predeterminados que definen una

situacin.

Finalmente, Giora (1991), propone la existencia del principio de

informatividad gradual, segn el cual los textos narrativos progresan

gradualmente de menos a msinformatividad. Este principio, en el caso

de los chistes, funcionara de manera marcada (requisito de

informatividad marcada, en adelante RIM), es decir, segn Giora, los

chistes progresan de menos a ms informatividad de modo brusco.

A partir de estas tres propuestas, la primera hiptesis de este trabajo

es que las VC constituyen un tipo de texto especfico dentro del gnero

textual humorstico, y como tales se caracterizan por:

- La presencia de unos determinados ndices externos. El conjunto

de los ndices externos constituira, en el nivel cognitivo, un script

formal asociado con el tipo de texto de las VC;

- La presencia de unos ndices internos, cuyafuncin en el nivelcognitivo sera la de activar los esquemas cognitivos de contenido.

La activacin de dichos esquemas permitira que se generara una

incongruencia humorstica;

- Una estructura informativa marcada, en el respeto del RIM de

Giora (1991).

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

50/760

23

La segunda hiptesis, por otro lado, se refiere a la existencia de

diferentes niveles de lectura de las VC, y se fundamenta en la ya citada

teora de los scripts (Shank, 1975; Rumelhart, 1975), en la Semantic

Theory of Verbal Humor (en adelante, STVH) de Raskin (1979, 1985), yen la propuesta de Attardo (1994, 1997), que a su vez bebe de muchas

aportaciones de autores precedentes, entre ellos Greimas (1966), Morin

(1970), y Suls (1972).

La STVH de Raskin (1979, 1985) establece las condiciones

necesarias para que un texto se pueda considerar humorstico, y stas

son: a) el texto tiene que ser compatible al menos en parte con dos

marcos o scripts diferentes, y b) los dos marcos o scripts tienen que estar

en oposicin.

Attardo (1994, 1997) desarroll la teora conocida como SIR, sigla

que significa Set-up, Incongruity, Resolution, es decir, las tres fases que

segn el autor constituyen un chiste: introduccin, incongruencia y

resolucin. A una primera fase que sirve a modo de introduccin, es

decir, el set-up, sigue una fase central en la que se genera la

incongruencia, y una fase final en la que el lector es capaz de resolver

esa incongruencia y volver a establecer el equilibrio.

As, pues, la segunda hiptesis plantea la existencia de diferentes

niveles de aproximacin o lectura de una VC, de acuerdo con la

estructura multimodal de la misma. Estos niveles se corresponden con la

activacin de diferentes scriptscognitivos ysu funcin es la de guiar al

lector a travs de las diferentes fases de comprensin de una VC.De esta segunda hiptesis, adems, nace otra, que est en el origen

de los estudios experimentales de los tiempos de lectura de las VC que

llevaremos a cabo en la fase final de la investigacin. Suponiendo que

estos diferentes niveles de lectura de las VC existen y estn

estructurados de menos a mayor complejidad, y sabiendo que a una

mayor complejidad de las tareas cognitivas de comprensin le

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

51/760

24

corresponde un mayor tiempo de ejecucin10, entonces es posible

plantear que los lectores necesitarn ms tiempo para acceder a los

niveles de comprensin ms profundos y complejos de las VC.

Finalmente, la tercera hiptesis que se intentar demostrar a travs deeste trabajo concierne a la comunicacin que se lleva a cabo a travs de

una VC. Esta hiptesis se basa a su vez en las teoras de Zhao (1988) y

Attardo (1994, 1997) acerca de los mensajes transmitidos a travs de los

chistes, y en la teora pragmtica de Levinson (2000) y de Lewis (1979).

Zhao (1988) (y ms tarde Attardo11), afirm que los chistes, a pesar

de ser un tipo de texto non bona-fide(en adelante, NBF) y violar, por lo

tanto, el principio cooperativo griceano, pueden transmitir contenidos

bona-fide (en adelante, BF), es decir, contenidos cooperativos y

verdaderos.

Levinson (2000), por otra parte, revis la propuesta de Grice (1975),

sustituyendo el concepto de mxima con el de principios comunicativos,

y desarrollando ulteriormente el concepto de implicatura conversacional

generalizada y particularizada. De acuerdo con Levinson (2000), una

implicatura conversacional generalizada (en adelante ICG) esun tipo de

contenido implcito que se infiere por defecto, de forma automtica, a

partir de los principios conversacionales. Al contrario, una implicatura

conversacional particularizada (en adelante ICP) se infiere solamente en

un contexto especfico.

Finalmente, Lewis (1979) trat el papel de las presuposiciones

(Stalnaker, 1970; Karttunen, 1973a y 1973b; Heim 1992) en lacomunicacin, y mostr que es prcticamente imposible decir algo que

sea inaceptable por falta de presuposiciones, porque, en el mismo

momento de la enunciacin, la presuposicin necesaria empezara a

existir debido a un mecanismo de acomodacin.

10Vase Fodor (1983).

11Vase Attardo (1994, 1997).

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

52/760

25

De acuerdo con estas propuestas, la ltima hiptesises que las VC

pueden comunicar a la vez contenidos de tipo BF y NBF, y que estos

contenidos se corresponden a la formulacin de diferentes tipos de

inferencias que ocurren en distintas fases del proceso de comprensin dela VC.

De esta tercera hiptesis deriva, a su vez, una subhiptesis vinculada

con la parte experimental de este trabajo, en particular con el desarrollo

de los experimentos de primado semntico (semantic priming, vase

McNamara, 2012). En este caso, la hiptesis que se plantea es la

siguiente: si las VC pueden transmitir contenido BF, entonces los

resultados de los experimentos de primado semntico reflejarn esta

relacin. La modalidad de realizacin de los experimentos se detallar

ms adelante, en el Captulo VI.

A esta tercera hiptesis de partida, y su correspondiente subhiptesis,

se vincula tambin el segundo objetivo general de la tesis, es decir, la

creacin de materiales didcticos para estudiantes de ELE, ya que si las

VC pueden transmitir contenido BF (Zhao, 1988), entonces, como se

ver en el Captulo VII, los alumnos pueden aprender de ellas.

1.2.3. El objeto de estudio

1.2.3.1. La terminologa del humor12

Despus de haber detallado cules son los objetivos del presente

trabajo, procederemos ahora a definir el objeto de estudio, es decir, las

vietas cmicas, un subtipo de gnero humorstico especfico. Esta

seccin empezar con la explicacin de los orgenes y el significado

12Vase Wickberg D. (1998); Martin, R. A. (2007) para una historia del concepto de humor

ms detallada.

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

53/760

26

actual del trmino humor, para luego describir las caractersticas

principales de las vietas cmicas y los elementos que las componen.

El significado del trmino humor, que deriva del latn humor, tal y

como especifica el diccionario de la Real Academia de la LenguaEspaola, es el siguiente: 1. m. Genio, ndole, condicin, especialmente

cuando se manifiesta exteriormente. 2. m. Jovialidad, agudeza. Hombre

de humor. 3. m. Disposicin en que alguien se halla para hacer algo. 4.

m. Buena disposicin para hacer algo. Qu humor tiene! 5. m.

humorismo (modo de presentar la realidad). 6. m. Antiguamente, cada

uno de los lquidos de un organismo vivo. 7. m. Psicol. Estado afectivo

que se mantiene por algn tiempo.

Como se puede ver observando la acepcin de significado 6,

antiguamente el trmino humor se utilizaba con un significado muy

diferente del que tiene hoy. En la antigedad, el trmino humores se

refera a los diferentes lquidos o fluidos presentes en el cuerpo humano

que comprendan la sangre, la bilis y la flema. Un estudioso griego

llamado Galeno (130 - 200 D. C.), precursor de la medicina moderna,

atribuy al exceso de determinados fluidos corporales unas

caractersticas psicolgicas, afirmando que los diferentes humores del

cuerpo y sus fluctuaciones eran los responsables de los cambios de

humor o estado mental en las personas.

A partir de la hiptesis de Galeno, con el tiempo, el uso de la palabra

humor adquiri cada vez ms unas caractersticas psicolgicas y

negativas. Sin embargo, hubo que esperar hasta el siglo XVI para que eltrmino humor llegara a ser utilizado por primera vez como sinnimo de

una personalidad extraa o excntrica, y para referirse al

comportamiento de alguien que no respetaba las normas sociales y que

los dems consideraban ridculo. El siglo XVI fue, por lo tanto, una

poca decisiva en la evolucin del significado de la palabra humor, ya

que antes del siglo XVI no exista ninguna relacin entre el trmino

humor y el concepto de ridculo.

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

54/760

27

Durante todo el siglo XVIII, el trmino ridculo fue utilizado para

referirse a lo que era capaz de generar una risa agresiva y humillante, de

acuerdo con la teora de Aristteles, segn el cual la risa se consideraba

algo negativo. No obstante, la risa estaba socialmente aceptada comoforma de entretenimiento para las clases sociales ms altas. Por esta

razn, Wickberg (1998) cree que es posible que, durante esta poca, y

debido a su amplia aceptacin social, la risa empezara a tener una

connotacin positiva. Poco a poco, el componente intelectual de la risa

empez a ganar terreno y se volvi ms importante que el elemento de

desprecio y humillacin.

A partir de la nueva acepcin de significado de la palabra humor,

acuada en el siglo XVI, se empezaron a utilizar tambin los trminos

humorista, para indicar a la persona objeto de la risa, y hombre de

humor, para indicar a quien posea el don de hacer rer a los dems

imitando las peculiares caractersticas del humorista. Esta distincin

entre los dos trminos perdurar hasta el siglo XIX, cuando la palabra

humoristase empieza a utilizar con su significado moderno, es decir,

para indicar a quien posee el don de hacer rer a los dems, y la

expresin hombre de humorcae en desuso.

Fue en el mismo siglo XIX cuando se produjo el ltimo cambio que

hizo que el trmino ingls humor empezara a tener el significado que

tiene hoy en da. Como consecuencia del uso del trmino wit,al que se

recurra para referirse al tipo de humor vinculado con una risa ms

agresiva, sarcstica e intelectual, el significado de la palabra humor seespecializ an ms, hasta llegar a referirse solamente al humor

vinculado con la risa benvola.

La palabra humor, su uso y su significado, han ido cambiando,

evolucionando y especializndose a lo largo de los siglos, pero, como la

misma entrada del diccionario de la Real Academia de la Lengua

Espaola demuestra, el trmino humor sigue teniendo hoy en da varias

acepciones muy diferentes. Lo cierto es que la naturaleza del humor

-

7/24/2019 tesis_elisagironzetti

55/760

28

sigue siendo un misterio. A pesar del esfuerzo de numerosos estudiosos

que se han dedicado a ello, y cuyos trabajos se researn en el captulo

dedicado al estado de la cuestin, todava nadie puede contestar de

manera exhaustiva a la pregunta qu es el humor? Sin embargo, graciasa los trabajos de investigacin de esos mismos estudiosos, hoy en da es

posible definir algunos de los elementos que hacen que haya humor, y