PEP LLINAS ARQUITECTURAS DE AUTOR AUTHOR … · la escalera, girados hacia el patio exterior,...

Transcript of PEP LLINAS ARQUITECTURAS DE AUTOR AUTHOR … · la escalera, girados hacia el patio exterior,...

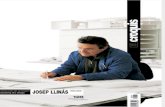

P E P L L I N A S

edición T6 EDICIONES, S.L.edition

dirección JUAN MIGUEL OTXOTORENAdirection

director ejecutivo JOSÉ MANUEL POZOexecutive director

coordinación CÉSAR MARTÍNcoordination

diseño gráfico D AVID RESANOgraphic design

traducción VERITAS TRADUCCIONEStranslation

distribución BREOGÁN DISTRIBUCIONES EDITORIALESdistribution Calle Lanuza, 11

28028 - MADRID

suscripción [email protected]

fotomecánica CONTACTO GRÁFICO, S.L.photography Río Elortz, 2 bajo, 31005, Pamplona - Navarra

impresión INDUSTRIAS GRÁFICAS CASTUERAprinting Polígono Industrial Torres de Elorz, Pamplona - Navarra

depósito legal NA. 1091/2006

ISBN 84-89713-93-6

T6 ediciones © 2005Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura. Universidad de Navarra31080 Pamplona. España. Tel 948 425600. Fax 948 425629

Todos los derechos reservados. Ninguna parte de esta publicación, incluyendo el diseño de cubierta, puede reproducirse,almacenarse o transmitirse de forma alguna, o por algún medio, sea éste eléctrico, químico, mecánico, óptico, de grabación o de fotocopia sinla previa autorización escrita por parte de la propiedad.

All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by anymeans, graphic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or information storage and retrieval systems without writtenpermission from the publisher.

AA ARQUITECTURAS DE AUTORAUTHOR ARCHITECTURES

35

SI PUDIERA DESAPARECER EL ARQUITECTO... LA ARQUITECTURA DE LA NATURALIDAD

IF THE ARCHITECT COULD DISSAPEAR... ARCHITECTURE OF SPONTANEITY

OBRA CONSTRUIDAFINISHED WORKS

BIBLIOTECA PÚBLICA “CAN GINESTAR”LIBRARY “CAN GINESTAR”

CONJUNTO DE EDIFICIOS EN FORT PIENCFORT PIENC CITY BLOCK

OBRA EN PROCESOIN PROCESS WORKS

BODEGAS EN MENDÍVILWINE CELLARS IN MENDÍVIL

BIBLIOTECA CENTRAL Y ARCHIVO MUNICIPAL DEL DISTRITO DE GRACIACENTRAL LIBRARY AND MUNICIPAL ARCHIVE IN THE DISTRICT OF GRACIA

INSTITUTO DE MICROCIRUGÍA OCULAR‘IMO’ INSTITUTE OF EYE MICROSURGERY

BIOGRAFÍABIOGRAPHY

44 CCAARRLLOOSS LLAABBAARRTTAA

1100 SSAANNTT JJUUSSTT DDEESSVVEERRNN.. BBAARRCCEELLOONNAA.. 22000000//22000033

1188 BBAARRCCEELLOONNAA.. 22000011//22000033

3300

3322 NNAAVVAARRRRAA.. 22000000//22000033

3366 BBAARRCCEELLOONNAA.. 22000033//22000044

4400 BBAARRCCEELLOONNAA.. 22000022//22000044

4466

88

4

Si pudiera desaparecer el arquitecto...

Si no creo en la palabra como soporte del discur-so arquitectónico (algo con lo que la contempora-neidad tan insistentemente nos sigue machacan-do) y pienso que la arquitectura se explica desdesu percepción y experimentación ¿qué sentidopueden llegar a tener mis frases ante la obra deun arquitecto de tan certeros silencios? Desdeque tuve la satisfacción de introducir esta publi-cación pienso, a cada rato, que el propio autor haconstruido, enseñado y escrito lo suficiente, y contal autoridad, como para que estas páginas, másque en otras ocasiones similares, sean, en elmejor de los casos, innecesarias o, en el peor,puedan introducir un velo de palabrería que seoponga a la naturalidad de su obra. Entiéndansemis palabras como un preludio o una afectuosacompañía de las suyas, leídas o escuchadas a suvera en la docencia compartida.

Pocos arquitectos han alcanzado un reconoci-miento tan unánime, no sólo de la crítica especia-lizada, sino, lo que es más difícil y meritorio, desus compañeros de profesión y academia. Acasoello se relaciona directamente con la inquebranta-ble coherencia y sinceridad, más allá de lo estric-tamente arquitectónico, evidenciada en su yalarga trayectoria. Y en esta firme voluntad de ama-ble, pero solemne, integridad, pueden entendersesus penúltimas búsquedas, que parecen trascen-der lenguajes y caminos ya transitados con éxitopara seguir profundizando en la búsqueda de unaarquitectura que, aparentemente despojada delos instrumentos estrictamente profesionales, sepresenta para su experiencia sensible.

En una reciente visita con un grupo de alumnosal Teatro Metropol, situados junto al espacio bajola escalera, girados hacia el patio exterior, Llinás,con certera convicción, comentó: “este espacioes más emocionante que la Capilla Sixtina”. Unaarquitectura que no presenta su musculación sinoque trata de eliminar los restos del esforzado ysufrido proceso, tanto del proyecto como de lapropia construcción, interesa sobremanera a unarquitecto que busca, precisamente en la amablenaturalidad, la expresión de la obra.

Así puede entenderse, en toda su plenitud, estecomentario que viene a profundizar en la intuiciónde que anónimas y pobres arquitecturas llenasde encanto y de vida trascienden, precisamentepor su debilidad, los esfuerzos poderosos. Nohay nada finalmente más poderoso que la mani-festación y aceptación de la propia debilidad.

Como ya dijo concisamente Alejandro de la Sota:“Llinás ve lo que nadie ve”. Y su forma de conoci-

miento deviene de los valores sensibles y per-ceptivos, para él no necesariamente vinculados alos intrínsecamente profesionales. O, mejor, con-vierte estos valores en los específicamente arqui-tectónicos. Así es capaz de comprender el lugaren el que se desarrolla el proyecto. En la bibliote-ca en Can Ginestar, Sant Just Desvern, se des-cubre el valor del cerramiento de la parcela, entrela masía existente y la calle Bonavista, formadopor un muro ondulado tan importante en la ima-gen del conjunto como la propia masía. De la per-cepción de este muro y del meticuloso y sensibleanálisis de los árboles existentes y la topografíase deriva la propuesta. De este modo puedeentenderse el brillante y delicado ejercicio de lasección del proyecto. Si el muro pudiera envolverla arquitectura y la topografía retomar su estadooriginal...

Frente a una contemporaneidad enfática y pre-tenciosa, que se vanagloria en episodios apa-rentemente modernos, Llinás propone una bús-queda de mayor profundidad que alcance su for-taleza ya no en la magnanimidad de los gestosya consolidados sino en la aparente debilidad.Ello pasa por liberar a la arquitectura de tanta“artillería” innecesaria para acercarla a la per-cepción de lo próximo. Así la obra ya no se nutreexclusivamente de principios y normas extraídosde la propia disciplina sino que pretende acer-carse a lo conocido por los sentidos. Por elloestos nuevos proyectos parecen carecer deesquemas de orden en el sentido más estricta-mente disciplinar.

Esta naturalidad se evidencia incluso en los pro-yectos, como el de la manzana Fort Pienc enBarcelona, en los que se presenta como un fácilejercicio lo que, en realidad, es una complejísimaresolución de un heterogéneo programa, merceda la inteligente manipulación de los instrumentosde proyecto que solucionan la especificidad decada uso adecuándolo a su escala necesaria.Advierto algo de mágica condición en la resolu-ción de este proyecto que convoca a la unidad derelaciones volumétricas y de materiales una agru-pación de edificios tan dispar.

La arquitectura, para el autor, no es sino el refle-jo de su comprensión de la realidad y su res-puesta ante ella. Esto se evidencia especial-mente en los proyectos cuyo entorno es elmedio natural. Así, en las propias memorias delos proyectos, los comentarios refieren a la per-cepción del lugar y la respuesta a la misma: “Ennuestro caso, mucho más que el cumplimientodel programa, ha sido la responsabilidad de

Carlos Labarta

5

I f t h e a r c h i t e c t c o u l d d i s a p p e a r . . .

If I do not believe in words as the basis for archi-tectonic discourse (a concept which contempo-raneity incessantly drills into our minds) and I holdthat architecture can be explained from its percep-tion and experimentation, what significance canmy words possibly have in the face of the work ofan architect endowed with such eloquent silence?Since I had the satisfaction of introducing this pub-lication I cannot help but think that the author him-self has constructed, taught and written enough,and with such authority, that these pages, morethan on other occasions, are either unnecessaryin the best of cases or, in the worst, may do nomore than veil the absolute spontaneity and natur-al quality of his work in a muddle of words. I dohope, however, that my words are taken as a pre-lude, or in devoted company to his, to be read ortaken in alongside them in shared indoctrination.

Few architects have attained such unanimousrecognition, not only from the specialised critic butalso from their professional and academic col-leagues, certainly a much more demanding andcommendable achievement. Perhaps this is directlyrelated to the unshakable persistence and sinceritywhich goes beyond the strictly architectonic, whichwe have seen time and again in Llinás’s lengthyprofessional career. And it is through this kind, yetsolemn integrity that his recent quests can beunderstood, seemingly transcending language andpaths successfully taken to further delve into thesearch for an architectural style which, outwardlystripped of everyday professional encumbrances, isoffered up for such an acute experience.

During a recent visit to the Metropol Theatre witha group of students, while standing next to thespace under the stair and facing the outer patioLlinás quite assuredly commented, “This space isfar more moving than the Sistine Chapel”.Architecture which does not impose, but ratherattempts to eliminate all vestiges of the effort andpainstaking evolution involved, both in the projectand in the construction itself, must necessarily beof the greatest interest to an architect who looksfor the expression of the work precisely in its nat-uralness and spontaneity.

Thus are we able to entirely understand such acomment, which stems from the conviction that,precisely because of their weakness, anonymousand penniless architects, so full of life and can-dour, are able to transcend such a striking effort. Inthe end, nothing is more powerful than the mani-festation and acceptance of one’s own weakness.

As Alejandro de la Sota so aptly put it, “Llinás seeswhat no one else does”. And this understanding

stems from a set of sensitive and perceptive val-ues, which for him are not necessarily linked to theintrinsically professional. Or perhaps it is that hetransforms these values into specifically architec-tonic standards. It is in this way that he is able tocomprehend the space in which the project is toevolve. In the library in Can Ginestar, Sant JustDesvern, we discover the value of the plot enclo-sure which lies between the existing countryhouse and Calle Bonavista, comprised of anundulating wall as important to the image as awhole as the country house itself. The designderives from the perception of this wall and from aprecise, meticulous analysis of the topographyand the existing vegetation, making it possible tounderstand this delicate, yet brilliant section of theproject. If the wall could envelop the architecture,allowing the topography to return to its originalstate…

In the face of an emphatic and pretentious con-temporaneity which boasts outwardly modernepisodes, Llinás offers us a search for greaterdepth, finding strength not in the magnanimity offormerly consolidated gestures but rather in theirapparent weakness. This requires freeing thearchitectural structure of so much superfluous“artillery” in order to more closely mould it to theperception of nearness.Thus the work is no longerfed exclusively by the principles and norms exact-ed from the discipline itself, but rather attempts anapproach towards what is known by the senses. Itis for this reason that new projects seem to lackthe philosophy of order in the strictly disciplinarysense.

This spontaneity can even be seen in designssuch as the Fort Pienc city block in Barcelona, inwhich it is seen as a simple exercise that in truthrepresents a complex solution to a heterogeneousprogramme, thanks to the intelligent handling ofthe instruments of design which offer a solution tothe specificity of each particular use, adapting it tothe appropriate scale. I sense something magicalin the solutions found for this project, which con-venes a grouping of such divergent buildings in aunity of volumes and material relations.

Architecture is, for the author, nothing more than areflection of his understanding of reality and hisresponse to it. This is particularly manifest in thoseprojects situated in a natural environment. Thus,the comments made in the project accounts them-selves make reference to how the location hasbeen perceived, and the author’s reaction to it. “Inour case it has been the responsibility of beinglocated within an extraordinarily balanced land-scape, much more than full compliance with the

6

la arqui tec tura de la natura l idad

situarse sobre un paisaje extraordinariamenteequilibrado, lo que ha determinado la propuestaarquitectónica”. La propuesta basa sus esfuer-zos en mantener ese equilibrio sin que se pro-duzcan indeseables e irreversibles presencias.Intentando la fusión, en un mismo plano, de lanaturaleza y la arquitectura. Esta estrategia seextiende también al entorno urbano. En unmedio construido, como el de la BibliotecaCentral del Distrito de Gracia en la plazaLesseps de Barcelona, el proyecto también seconcibe desde la voluntad de adecuar y comple-tar lo inmediato. Así hay que comprender la geo-metría romboidal de la planta que completa elvolumen iniciado por las edificaciones adyacen-tes. Trascendiendo esta geometría se intentafundir el propio volumen de la biblioteca con elde los edificios posteriores.

Llinás, en esta voluntad de adecuación al medio,nos presenta una arquitectura que pueda serexperimentada sin la necesidad de enfrentarse aella. A menudo la arquitectura se presenta paraser admirada y, posteriormente, vivida, existiendouna frontera que precisa ser traspasada necesa-riamente. Así, en la capacidad de experimentar laobra sin la necesidad previa de descubrirla seproduce la disolución de la frontera entre percep-ción y participación. Todas estas intenciones sealejan en Llinás del carácter representativo de laarquitectura.

Eludir los problemas de representación que, amenudo, van asociados de manera esclavizantea una suerte de dependencia a la corrección pro-fesional, es otra de las características de la obraque aquí se presenta, además de prueba de lagozosa libertad del autor. Hace ya más de dosdécadas Llinás, en referencia a Coderch, escribióestas palabras que se han convertido en su pro-pia luz: “Y su trabajo se centra, no en la proposi-ción de imágenes o en la elaboración de lengua-jes, sino en la definición de plantas, hasta resol-ver en ellas todos los problemas, toda la arqui-tectura, para que el levantamiento de los alzadossólo sea la prueba de que en el edificio ya se hahecho inútil o superflua la representación”.

Este proceso implica una búsqueda paciente. Meadmira la capacidad de Llinás de volver a pro-yectar sobre lo proyectado, en un ejercicio sin fin,modificando, limpiando, haciendo desaparecertodo resto enfático o innecesario. Incluso con pro-yectos ya entregados es capaz, con toda la difi-cultad burocrática añadida y siempre temida, devolver a modificarlos. Ésta es la actitud de unarquitecto que trabaja intensa, y festivamente,para que la arquitectura se presente con lo míni-mo necesario. Como si, en el fondo, todo fuera un

retorno a sus pasos en el Teatro Metropol de suíntimamente apreciado Jujol.

Esta conjunción de intereses en la arquitectura deLlinás se guía por una vinculación afectiva, acasomás que racional, con el mundo que le rodea encada proyecto, abrazando y envolviendo todo elmundo con la mirada (el muro y los árboles en labiblioteca de San Just Desvern, la topografía y elpaisaje en la bodegas en Mendívil y el Instituto deMicrocirugía Ocular en Barcelona, la ciudad y elmar en la Biblioteca de la Plaza Lesseps...). Laexperiencia espacial se constituye en el centro deuna arquitectura que no enfrenta al usuario conuna interpretación imposible sino que le facilita laatención y el aprecio por lo próximo. Y éste es elmejor regalo que brinda la arquitectura de Llinásposibilitando al morador la experiencia sensible yamable del espacio que habita. A menudo laarquitectura del mundo contemporáneo no nosacoge porque es reflejo del mundo inhóspito quenos rodea. Incluso no permite que la entendamosdevolviéndonos a un estado de muda perplejidad.Pero, como hemos anunciado, el arquitecto nopersigue la bondad en criterios de representa-ción, ni de interpretación, sino de experimenta-ción. Por ello en la arquitectura que aquí se pre-senta no se trata de incrementar la complejidadde unas relaciones imposibles fruto exclusivo deespeculaciones del arquitecto sino, por el contra-rio, de envolver la presencia de la persona acti-vando sus capacidades perceptivas.

Todo ello no sería posible sin su capacidad cons-tructora y su profundo conocimiento de los mate-riales a cuyas cualidades expresivas confía laexperiencia sensible de la obra. Estos secretosno son desvelados directamente. Aun cuando lasdecisiones tectónicas requieran de esfuerzossuplementarios no ejemplificarán su fortaleza.Demasiado pretencioso para una arquitecturaque prefiere una amable naturalidad a una exhi-bición de medios.

Para Llinás, en el fondo, la búsqueda última seorienta hacia la construcción de una arquitecturadesnuda de arquitectura; liberada de los meca-nismos reconocibles propios del arquitecto paraacercarse a una natural presencia en el entorno.De este modo la obra se presenta cargada de lasincera y verdadera búsqueda de su autor porcomprender, con todas sus capacidades, losafectos y percepciones del hombre. Y una vezcomprendidos hacer desaparecer los rastros dela presencia del arquitecto para que la obra, y suexperimentación, permanezcan como exclusivosprotagonistas. Quedarán, invisibles, pero sinduda perceptibles, la profunda mirada y los largossilencios del autor.

7

programme, that has been the determining factorin the architectonic proposal”. The proposeddesign grounds its efforts in maintaining this bal-ance without producing undesirable and irre-versible consequences. In short, it is a search forfusion between nature and architecture within thesame dimension.

This strategy extends to urban settings as well. Ina built-up area, such as that of the Gracia District’sMain Library in Lesseps Square, Barcelona, theproject design is also developed in response to adesire to accommodate and fill in what is immedi-ately before us. It is thus that we are able to com-prehend the rhomboidal geometry of the floorwhich fills in the volume begun by the adjacentbuildings. It is by transcending this geometry thatan attempt is made to merge the volume of thelibrary with that of the neighbouring buildings.

Through this adaptation to setting, Llinás offers anarchitectural design that can be experienced with-out having to actually confront it. Often architec-ture exists first to be admired, and subsequently,lived, compelling us at some point to cross overthis inevitable frontier. It is through this capacity ofexperimenting the work, having previouslybypassed the need to discover it, which leads to ablurring of this frontier between perception andparticipation. All of these designs set Llinás apartfrom the representative character of architecture.

Evading these challenges of representation whichare often tied inexorably to a manner of depen-dence on professional correctness is another ofthe characteristics of the work here presented, aswell as proof of the satisfying freedom of its author.More than two decades ago Llinás wrote the fol-lowing lines in reference to Coderch, “His workcentres not on the presentation of images or thecreation of languages, but rather on the definitionof floors, until all problems within them and withinthe structure itself have been resolved, such thatin raising the walls it becomes clear that represen-tation has now been rendered useless, superflu-ous”. These words have since become Llinás’sown source of inspiration.

This process requires a patient search. I admireLlinás’s ability to redesign over his own original inan endless quest, modifying, grooming, doingaway with any and all emphatic and unnecessaryremnants. He is even capable of altering projectsalready tendered, despite all the added and fearedbureaucratic complications involved. Such is theattitude of an architect who works both intenselyand light-heartedly so that the structure is pre-sented with the bare minimum. It is as if, at the endof the day, everything went back to the steps at the

Metropol Theatre, designed by his admired col-league Jujol.

This coming together of interests in the architec-ture of Llinás is led by a link, perhaps more emo-tional than rational, with the world that surroundshim in each project, embracing and envelopingeveryone and everything with a vision (the walland trees at the San Just Desvern library, thetopography and landscape at the Mendívil winer-ies and the Institute of Ocular Microsurgery inBarcelona, the city and the sea at the Library inLesseps Square…). The experience of spacebecomes the central focus of an architecturewhich does not assail the viewer with an impossi-ble interpretation, but rather eases the attentionand appreciation of something accessible. This isthe finest aspect of Llinás’s designs, allowing thedweller to take away a kind, sensitive impressionof the space he is inhabiting. Contemporary archi-tecture often seems inhospitable because itreflects the antagonistic world which surrounds us.It remains quite out of the bounds of our compre-hension, leaving us in a state of mute perplexity.As we have previously said, however, the architectis not searching for goodness or kindness in thecriteria of representation or of interpretation, butrather in experimentation. It is therefore not theaim of the architecture presented here to accentu-ate the complexity of a set of impossible relationsderived exclusively from the speculations of thearchitect, but very much on the contrary, it lies incapturing the presence of the person by activatingtheir capacity for perception.

None of this would be possible without the con-structive finesse of the architect and an extensivefamiliarity with the materials in whose expressivequalities Llinás entrusts the delicate experience ofthe work. These secrets are not directly revealed;not even when tectonic decisions require addition-al effort will this strength be exemplified. It wouldbe far too pretentious for a style which prefers anobliging spontaneity to a demonstration of means.

In the end, the ultimate search for Llinás is aimedat the construction of an architecture devoid ofarchitecture, freed from the recognizable mecha-nisms common to architecture in order to pushtowards a natural presence within the environ-ment. The project is thus imbued with the true andsincere quest of the author to understand fully thesympathies and perceptions of man. And oncethese have been understood, make all vestiges ofthe presence of the architect disappear, such thatthe work itself and the experimentation involvedbecome the sole protagonists. What shall remain,invisible yet undoubtedly perceptible, is the pro-found vision and the lengthy silences of theauthor.

archi tec ture of spontanei ty

MERCADO, BIBLIOTECA Y GUARDERÍA EN LA MANZANA COMPRENDIDA ENTRE LAS CALLES SICÍLIA, SARDENYA, ALI-BEI I RIBES (FORT PIENC)MARKET, LIBRARY AND NURSERY SCHOOL IN THE CITY BLOCK FALLING BETWEEN SICILIA, SARDENYA, ALI-BEI AND RIBES STREET (FORT PIENC)Proyecto de arquitectura/ Architecture project: Josep Llinás y CarmonaColaboración/ Collaboration: Joan Vera García, Juan Marco Marco y Andrea TissinoAparejador/ Quantity surveyor: Jaume Martí AlmestoyProyecto de instalaciones/ General installations proyect: PROEN, SLProyecto de estructuras/ Structure project: Jordi Bernuz BertolínPropiedad/ Owner: Proiexample, S.AEmpresa constructora/ Building contractor: FCCFecha de proyecto/ Project date: Junio/ June 2001Fecha de ejecución/ Executive project date: Marzo/ March 2003Premios/ Awards: “Ciutat de Barcelona 2003”

BARCELONA

BIBLIOTECA EN ‘CAN GINESTAR’LIBRARY AT ‘CAN GINESTAR’Proyecto de arquitectura/ Architecture project: Josep Llinás y CarmonaColaboración/ Collaboration: Joan Vera García, Pedro Ayesta BorrásAparejador/ Quantity surveyor: Jaume Martí AlmestoyProyecto de instalaciones/ General installations proyect: JMC Ingenieros, S.L.Proyecto de estructuras/ Structure project: Jordi Bernuz BertolínPropiedad/ Owner: Ayuntamiento de Sant Just DesvernEmpresa constructora/ Building contractor: FCCFecha de proyecto/ Project date: Junio/ June 2001Fecha de ejecución/ Executive project date: Enero/ January 2002 - Marzo/ March 2003

SANT JUST DESVERN

9

10

BARCELONA. 2000/2003

La biblioteca se sitúa en el espacio libre del solar ocupado por lamasía “Can Ginestar”, edificio que ya actualmente se destina a ser-vicios públicos del Ayuntamiento de Sant Just Desvern (entre ellosel de biblioteca).

Si la masía es una pieza a conservar y valorizar, el jardín que larodea es también un referente para Sant Just; y los años acumula-dos sobre su vegetación dan a su arbolado un valor singular.

Situar en este contexto una nueva edificación de unos mil metroscuadrados, que debía compartir acceso con la masía (según mani-festó el Ayuntamiento) y, por tanto, debía estar en continuidad conésta era, es, el problema fundamental del proyecto.

En cuanto a la masía, en su límite oeste, allí donde la topografíatiene más pendiente, tiene una serie de construcciones añadidas deescaso valor, cuya sustitución nos podía dar cabida a una parte delprograma de la biblioteca y, al mismo tiempo, espacio para formar laconexión entre masía y nueva edificación.

Por otro lado, el jardín, situado en el norte de la masía, muy consti-tuido en lo que hace referencia al acceso y el límite este, está for-mado por árboles de gran porte, sobre un terreno que, de nuevo, porsu pendiente y poca accesibilidad, se utiliza en mucho menos gradoque el acceso o el jardín situado en el sur.

Así pues, el jardín situado en el norte de la masía, en solución decontinuidad con las construcciones auxiliares que antes comentá-bamos, es un espacio de escasa utilización por su pendiente y faltade asolamiento. Es un jardín calificado por la presencia de grandesárboles (especialmente un cedro, pinos y palmeras) pero con poca“habitabilidad”.

El límite de este jardín con la calle Bonavista es una pared de obrasin valor, al contrario de lo que pasa con el resto del cierre a partirde la masía, formado por un muro ondulado tan importante en laimagen del conjunto como la propia masía.

Las actuaciones sobre el jardín conservan los árboles más impor-tantes (se ponen a su sombra), y conserva el cierre, la volumetría yel perfil de la calle Bonavista hasta la masía; a partir de ella, el lími-te de la edificación de nueva planta se trata como continuación dela valla existente y cuando se llega al pasaje perpendicular a la calleBonavista, se forma un mirador ahora inexistente desde la callehacia la biblioteca y el jardín.

La biblioteca, en lo que sería la fachada al jardín, se trata como unagalería vidriada que busca el contacto visual intenso y extenso conlos grandes árboles, y formalmente se trata con elementos ligerosque huyen de la imagen maciza de la masía y pueden ser entendi-dos como su contrapunto formal.

BIBLIOTECA 'CAN GINESTAR' LIBRARY ‘CAN GINESTAR’

ppllaannttaa ddee ssiittuuaacciióónnsite plan

0 20

m

11

The library is located in an open space on the plot occupied by the Can Ginestar manor house, a building which is currently used bythe Sant Just Desvern Town Hall for public services (including the library).

The manor house was an element to be conserved and valued, while the garden surrounding it was also a key site in Sant Just, andthe accumulation of years of vegetation confers a singular value on its wooded area.

Placing within this setting a new building measuring approximately one thousand square metres, which had to share the entry withthe manor house (as stipulated by the Town Hall) and had to thus blend in well with the latter, was this project’s main challenge.

On the western edge of the manor house, where the topography is steeper, there was a series of auxiliary structures with scant value.Replacing them would enable us to fulfil part of the agenda for the library, while at the same time providing space for forging the con-nection between the manor house and the new building.

Likewise, the garden, located on the northern part of the manor and well-established in terms of the entry and eastern edge, is madeup of stately trees over terrain that once again, due to its slope and difficult accessibility, is used to a much lesser extent than theentrance or the garden located on the southern side.

Thus, in a solution aimed at providing continuity with the auxiliary buildings mentioned above, the garden located on the northern partof the manor is a space that is seldom used due to its slope and lack of sunlight. It is a garden marked by the presence of large trees(especially cedars, pines and palm trees) yet without being very “liveable”.

The edge of this garden on Bonavista street is a brick wall without value, unlike the rest of the manor house’s enclosure, which ismade up of an undulating wall as important as the house itself in the image of the complex.

The actions on the garden conserved the most important trees (they are placed in their shade), and the enclosure, volumetrics andshape of Bonavista street is preserved as far as the manor house. Thereafter, the edge of the new building is dealt with as a contin-uation of the existing fence, and when it reaches the passageway running perpendicular to Bonavista street, a previously inexistentlookout point is created from the street towards the library and garden.

In what would be the façade facing the garden, the library is treated as a glassed-in gallery which seeks both intensive and exten-sive contact with the stately trees, and it is formally dealt with through lightweight elements that contrast with the solid image of themanor house and can be viewed as their formal counterpoint.

12

12

aallzzaaddoo pprreevviioo aall pprrooyyeeccttooprevious elevation

aallzzaaddoo ssuurrsouth elevation

0 20

m

ppllaannttaa sseegguunnddaasecond floor

sseecccciióónn llooggiittuuddiinnaalllongitudinal section

0 20

m

0 20

m

15

La manzana del ensanche situada entre las calles Sicília, Sardenya, Ali-Bei y Ausiàs March presenta una geometría irregular resultado de su división en dos partes por lacarretera de Ribes.

En la manzana se encuentra un edificio lineal destinado a Centro Cívico, que ocupa el centro de la misma, con un criterio ajeno al sistema de construcción en corona quedetermina la morfología del ensanche. La ordenación inicial preveía la implantación de otros equipamientos adyacentes a este inicial y de un edificio de planta baja más cincoplantas con fachada en la calle Sardenya, éste sí, con los criterios comunes de construcción del ensanche Cerdà.

El programa de equipamientos previsto alrededor del Centro Cívico era una biblioteca (que tenía que compartir servicios con el Centro Cívico), una Guardería, un Colegio deEnseñanza Primaria y un Mercado. Además, el edificio de planta baja más cinco plantas encarado a la calle Sardenya se dividía en dos, uno destinado a residencia de estu-diantes, de gestión privada, y otro a Residencia Geriátrica construido por una Fundación privada y cedido posteriormente al Ayuntamiento.

De manera que el problema a solucionar sumaba una geometría de límite atípico en relación a la definida en el Ensanche, en cuyo interior se encontraba un edificio singu-lar imposible de “digerir” si se aplicaban criterios de ordenación en corona, un límite (calle Sardenya) que sí respondía a estos criterios y un programa radicalmente hetero-géneo en cuanto a las diferentes tipologías de edificación que generaba. Y una constatación inmediata a la hora de plantear la solución más evidente (construir el límite,como en todo el Ensanche): los metros cuadrados edificables previstos en la ordenación inicial no daban ni con mucho para extender a estos límites el tipo de edificaciónprevista en relación a la calle Sardenya.

La solución ha necesitado de un grado extremo de artificiosidades y violencia en la propuesta, para conseguir establecer relaciones comunes entre geometrías, tipos edifi-catorios y usos radicalmente heterogéneos. Fundamentalmente el criterio de ordenación ha sido subordinar férreamente todas las edificaciones a su dependencia de la calleRibes (que se amplia en el tramo central para generar un espacio autónomo, estático, de plaza).

Esta voluntad nos ha llevado a “plastificar” la geometría de la Residencia Geriátrica para doblarla y encararla a este espacio público, a vincular (y magnificar) todas las entra-das a este mismo espacio público y a trabajar con instrumentos de proyecto que solucionen la especificidad de cada uso y expresen su escala (tan diferente entre, por ejem-plo, un mercado y una guardería) y al mismo tiempo determinen relaciones comunes de volumetría y materiales entre una agrupación de edificios tan dispar.

19

BARCELONA. 2001/2003 MANZANA FORT PIENCFORT PIENC DWELLING

The city block in the Ensanche district located between Sicília, Sardenya, Ali-Bei and Ausiàs March streets presented an irregular geometry resulting from its division into twoparts by Ribes street.

There is a linear building devoted to a Civic Centre in the middle part of this street, following criterion other than the system that determines the morphology of the Ensanche,which involves peripheral buildings with an empty core space. The initial planning called for the installation of other facilities adjacent to this centre and of a building consist-ing of a ground floor plus five stories on Sardenya street, the latter, however, using the building criteria commonly applied in Cerdà’s Ensanche neighbourhood.

The plans for facilities to be located near the Civic Centre included a library (which had to share services with the Civic Centre), a nursery school, an elementary school anda market. What is more, the building with a ground floor and five stories facing Sardenya street was divided in two, one part to be used as a privately managed student dor-mitory and the other as a senior citizens’ home built by a private foundation and subsequently ceded to the Town Hall.

Thus, the problem to be solved involved a peripheral geometry atypical compared to the one previously defined in the Ensanche, inside which there was a unique buildingthat was impossible to “digest” if the criterion of peripheral block design was applied; one part of the perimeter (Sardenya street) which did follow these criteria; and a radi-cally heterogeneous agenda in terms of the different types of buildings generated. What was immediately evident when considering the most obvious solution (building aroundthe periphery, as throughout the entire Ensanche) was that the square metres that were slated as buildable in the initial planning stage were not sufficient to extend to theseouter limits the type of building planned in relation to Sardenya street.

The solution called for an extreme degree of skill and daring in the design in order to achieve common relations amongst geometries, types of buildings and radically hetero-geneous functions. Basically, the criterion of design was to strictly subordinate all the buildings to the site to Ribes street (whose centre was widened in order to generate anindependent, static square).

This aim led us to “plastify” the geometry of the senior citizens’ home in order to fold it and make it face this public area, to link (and magnify) all the entrances to this squareand to work using design instruments that solved the specific needs of each function and expressed their scale (which differs so widely between a market and a nursery school,for example) and at the same time determine common relations of volumetrics and materials among such a disparate cluster of buildings.

21

iissoommééttrriiccoo.. pprrooppuueessttaa BBisometric view. proposal B

iissoommééttrriiccoo.. pprrooppuueessttaa CCisometric view. proposal C

iissoommééttrriiccoo.. pprrooppuueessttaa FFisometric view. proposal F

iissoommééttrriiccoo.. pprrooppuueessttaa GGisometric view. proposal G

22

ppllaannttaa qquuiinnttaafifth floor

ppllaannttaa pprriimmeerraafirst floor

ppllaannttaa bbaajjaaground floor

0 50

m

NAVARRA. 2000/2003 BODEGAS EN MENDIVILWINE CELLARS IN MENDIVIL

ppllaannoo ddee ssiittuuaacciióónnsite plan

Así como en otro tipo de edificaciones, el análisis, la organización y la resolución del programa es la base del proyecto, en el caso particular de una bodega, la forma de cadauna de las unidades que la componen, así como los recorridos y relaciones entre todas sus partes, responden a necesidades claras y fáciles pero con poca capacidad dedeterminar la forma de la edificación. Tan sólo la enorme diferencia de escala entre las naves de elaboración, almacenamiento, etc., de orden industrial y el área adminis-trativa y de representación, a escala casi doméstica, constituye un problema de orden arquitectónico.

En nuestro caso, mucho más que el cumplimiento del programa ha sido la responsabilidad de situarse sobre un paisaje extraordinariamente equilibrado, lo que ha determi-nado la propuesta de arquitectura.

Poner o situar en ese entorno naves industriales de diez o doce metros de altura y 40 ó 45 x 20 metros de planta significaba una alteración irreversible del equilibrio antesmencionado. Decidimos trabajar con la idea de enterrar o empotrar el gran volumen de construcción necesario para la bodega como primera decisión para amortiguar elimpacto en el paisaje.

Eso significaba analizar y reconocer la topografía del terreno disponible en profundidad y elegir el mejor emplazamiento para acordar construcción y paisaje. Decidimos poner-nos junto al camino que atraviesa la finca, y junto a una masa de árboles existentes para ligarnos a dos referencias existentes en el paisaje natural. Y a partir de aquí, bus-car la topografía con mayor pendiente, de manera que las cubiertas de la bodega se situaran a la cota topográfica de mayor altura y la construcción tuviera fachadas tan sólocomo consecuencia de la diferencia de nivel.

Por otra parte, la no necesidad de luz natural para las naves (más bien al contrario, ésta podía alterar las condiciones de humedad y temperatura requeridas) hacen que laparte emergente de la bodega se presente como un volumen opaco e inexpresivo: entender la bodega como una gran masa pétrea empotrada en la suave topografía noscondujo a proponer como cerramiento de la misma en vertical y en horizontal un recubrimiento pétreo, de piedra sin pulir ni devastar con la idea de que este material acep-tara con naturalidad la fusión con las condiciones naturales del entorno.

Tan sólo las áreas administrativas y representativas se tratan como una excepción: situadas sobre el borde sur se cierran con vidrio y celosías de madera barnizada corre-deras, como único material de acabado.

Segundo proyecto:Cambios en el programa de necesidades, que obligaban a dar mayor altura a una de las naves, nos condujo a elaborar un segundo proyecto, en fase de redacción a la horade preparar este libro. Como en el primero, el argumento se basa en la topografía. Si antes ésta se vaciaba en parte para dejar a la vista el volumen de la bodega, ahora esconsiderada como una alfombra que se levanta puntualmente allá donde la altura de las naves supera las cotas naturales. En esta solución, el acceso desde aparcamientoal límite sur de la bodega (donde se encuentran las áreas administrativas, comedor, sala de catas) se puede producir en superficie, en un movimiento guiado por las pen-dientes de la cubierta, o bajo la misma mediante un paso cubierto que permite la visión desde una cierta altura de las naves enterradas.

0 50

m

32

33

Just as how in other types of buildings, analysing, organising and resolving the agenda is the cornerstone of the design, in the particular case of a wine cellar, theshape of each of the units making it up as well as the routes and relations amongst all the parts correspond to needs that are clear and simple yet that are little ableto determine the shape of the building. Only the enormous difference in scale between the premises needed to produce, store and carry out other industrial-type func-tions, and the administrative and sales areas, which are on a virtually domestic scale, constitutes the true architectural challenge.

In our case, much more than fulfilling the agenda, the challenge has been the responsibility for placing the cellars on an extraordinarily balanced landscape, which hasdetermined the architectural proposal.

In this setting, placing or locating industrial premises measuring ten or twelve metres high and forty or forty-five by twenty metres large signified an irreversible alter-ation in this balance.

We decided to work with the idea of burying or embedding the large constructed volume needed for the wine cellar as an initial decision in order to lessen the impacton the landscape.This meant making an in-depth analysis and survey of the topography of the land available and choosing the best location to harmonise the buildingwith the landscape.We decided to situate ourselves near the road crossing the estate, and near an existing stand of trees in order to attach ourselves to two references already existingin the natural landscape. From there, we sought the topography with the greatest slope so that the roofs of the wine cellar would fall at the highest topographical leveland the building’s façades would emerge only as a result of the difference in level.

Likewise, the lack of a need for daylight for the large industrial premises (actually, the opposite is needed since daylight could alter the required moisture and temper-ature conditions) led the emergent part of the wine cellar to appear as an opaque, inexpressive volume. Specifically, viewing the wine cellar as a large stone massembedded in the gently rolling topography led us to propose a stone covering for its vertical and horizontal enclosure, made of neither polished nor distressed stonefollowing the notion that this material could naturally accept the fusion of the natural conditions of the setting.

Only the administrative and sales areas were dealt with differently: located on the southern edge of the land, they are enclosed with glass and sliding varnished woodlattices as the sole finishing material.

Second project:Changes in the agenda of needs, which required making one of the large industrial buildings taller, led us to develop a second design, currently in the drafting stage.Just as in the first design, the concept this time was also based on the topography. While in the former, the land was partly excavated to leave the volume of the winecellar exposed, now it is regarded as a carpet that occasionally emerges wherever the height of the warehouses exceeds the natural levels of the land. In this solu-tion, access from the car park on the southern side of the wine cellar (where the administrative areas, dining hall and tasting room are located) can take place eitheron the surface, in a movement guided by the slopes of the roof, or under the roof, through a covered passageway that confers views of the buried warehouses from acertain height.

pprrooppuueessttaa iinniicciiaall//pprrooppuueessttaa ffiinnaallfirst proposal/final proposal

34

ppllaannttaa ssaallaa ddee ccaattaass wine taste room floor

ppllaannttaa bbooddeeggaawine cellar floor

0 25

m

37

BARCELONA. 2003/2004 BIBLIOTECA CENTRAL Y ARCHIVO MUNICIPALDEL DISTRITO DE GRACIACENTRAL LIBRARY AND MUINICIPAL ARCHIVE IN THE DISTRICT OF GRACIA

The proposal emerged from two considerations:

1. Understanding the importance of the façade of the plot of land where the library is located as a summation of later large-scalefaçades of the buildings reached via Avenida República Argentina.2. Embracing the radical change that the direct connection of the “green corridor” with Lesseps square (bordered by AvenidaHospital Military and Bolívar street) will have in the use and understanding of this part of the city.

In terms of the former consideration, the goal was for the volume of the library itself to merge with that of the later buildings. Thisobjective translates into the layout, as its edge is defined with a rhomboidal geometry that completes the volume initiated bythese buildings. Through this operation, the library faces the large open area of Lesseps square from the scale and protectionconferred on it by the volume created by the aforementioned buildings.

In terms of the latter consideration, the opening of this green corridor to the north of Lesseps square was viewed as a public axisthat expresses and embraces the unique topography on which this part of the city lies (mountainside, green spaces blended withbuildings), of which this square itself is either the beginning or the end. It could be claimed that the mountains (Collserola) reachas far as Lesseps, and from there on the city has a different consistency, more closely liked to the layout of the streets than tothe topography or the slope.

Expressing this condition of Lesseps being a boundary between the mountain and the city led us to volumetrically shape thelibrary virtually as a building that -arriving from Collserola- is located over the city with the attributes of the mountains.

La propuesta nace de dos consideraciones:

1. Entender la importancia, que como telón de fondo del solar de la biblioteca, tiene la fachada, suma de las fachadas poste-riores de gran tamaño de los edificios con acceso por la Avenida República Argentina.2. Recoger el cambio radical que en el uso y el entendimiento de esta parte de la ciudad, tendrá la conexión directa del “corre-dor verde” (limitado entre la Avenida Hospital Militar y la calle Bolívar) con la plaza Lesseps.

En el primer caso, se intenta fundir el propio volumen de la biblioteca con el de los edificios posteriores. Este objetivo se tradu-ce en la planta al definir su límite con una geometría romboidal que completa el volumen iniciado por estas edificaciones: conesta operación, la biblioteca se enfronta a la gran superficie abierta que significa la plaza Lesseps desde la escala y protecciónque le da el volumen que forman los edificios ya mencionados.

En el segundo caso, se ha entendido la apertura de este corredor verde, al norte de la Plaza Lesseps, como un eje público queexpresa y recoge la topografía singular sobre la que se asienta esta parte de la ciudad (ladera de montaña, verde mezclado conconstrucción), del que precisamente la plaza se presenta como final o como inicio. Se podría decir que las montañas (Collserola)llegan hasta Lesseps y a partir de aquí la ciudad tiene otra consistencia, más ligada al trazado de las calles que no a la topo-grafía o a la pendiente.

Expresar esta condición de límite montaña-ciudad de la plaza Lesseps, nos ha llevado a configurar volumétricamente la biblio-teca, casi como un edificio que -llegando de Collserola- se sitúa sobre la ciudad con los atributos de las montañas.

38

ppllaannttaa sseegguunnddaasecond floor

ppllaannttaa pprriimmeerraafirst floor

0 25

m

ppllaannttaa bbaajjaaground floor

39

ppllaannttaa pprriimmeerraa.. iissoommééttrriiccoo first floor. isometric view

ppllaannttaa sseegguunnddaa.. iissoommééttrriiccoosecond floor. isometric view

40

The project began with an idea contest held in September 2002, and its development has been a work in progressever since. The main idea of the project, which despite significant morphological changes has been retainedthrough all the proposals, was based on:

Location: Ronda de Dalt, as the ring road around Barcelona marking its boundary with Collserola mountain, wasviewed as a motorway and access route, but more importantly as a boundary between the city and the mountain,between buildings and natural terrain. This is not entirely accurate, however, since the city has colonised (as in ourcase) part of this natural terrain. Yet Ronda de Dalt can nonetheless be viewed as marking a certain boundary ofthe city, beyond and to the west of which the natural terrain predominates over built-up land. This predominanceis physically translated on the land into a considerable slope which unquestionably determines the buildings occu-pying it.

Agenda: The IMO agenda, essentially articulated (as in similar cases) into floors of surgeries, consultation roomsand administrative or study areas and car parks, was distinguished by the fact that the majority of its activities tookplace without daylight (consultation rooms, surgeries), which, however, was extremely necessary, as a counter-point, in the areas devoted to waiting, resting or private work. Based on these considerations, the idea of the con-test was expressed in the cross-section of the building: the majority of it was embedded in the land, and only theentrance, waiting rooms and areas devoted to administration, offices, and library -off-limits to patients- were facingthe city (the views of which, along with the views of the sea, are extraordinary).

The building is set apart from the Ronda de Dalt and encroaches into the middle of a small forest linked to the veg-etation of Collserrola, which distances the building from the city and submerges it in the natural environment sur-rounding it. Particular attention was paid to the entry from the street to the hall, with the understanding that theobjectives of the Institute must be expressed there: attention, care and comfort for the sight and the instrument thatmakes it possible, the eye. Thus, the entrance, waiting rooms and other areas are unified through a semi-open,semi-closed space, a type of “umbracle” which introduces shade and penumbra to the spaces facing the outside,just as sunglasses, visors or at times one’s hand are used to reduce the (so often bothersome in climates like ours)excessive intensity of the light or sunstroke. The outer limits of the plot were modified (due to urban planning reg-ulations) during the design process. This required us to move the building forward considerably closer to Rondade Dalt, leading the front of the building to appear disproportionately large. The second phase in the projectattempted to reduce this impact by relating the volume of the building to the lay of the land without in any way mod-ifying the original ideas outlined above.

BARCELONA. 2002/2004 INSTITUTO DE MICROCIRUGIA OCULAR ‘IMO’‘IMO’ INSTITUTE OF EYE MICROSURGERY

El proyecto se inicia con un concurso de ideas, realizado en septiembre de2002. La idea principal del proyecto, que pese a los importantes cambiosmorfológicos se ha mantenido en todas las propuestas, se basaba en:

Emplazamiento: La Ronda de Dalt en tanto que cinturón que limitaBarcelona en relación a la Sierra de Collserola, fue entendida como una víade circulación y de acceso pero sobre todo como límite entre la ciudad y lamontaña, entre construcción y terreno natural. Apreciación que no es deltodo cierta, pues la ciudad ha colonizado (como pasa en nuestro caso)parte de ese terreno natural. Pero, aun así se puede considerar que laRonda de Dalt marca un cierto límite de la ciudad, a partir del cual y haciael oeste domina el territorio natural en relación al territorio construido. Estedominio se traduce físicamente en el terreno a través de una pendienteconsiderable que debe cualificar, sin duda, la edificación que lo ocupe.

Programa: El programa del IMO, esencialmente articulado (como en casossimilares) en plantas de quirófanos, consultas y áreas de administración oestudio y aparcamientos, se significaba por el hecho de que la mayor partede su actividad se realizaba sin luz natural (consultas, quirófanos) y, al con-trario era muy necesaria, como contrapunto, en las áreas de espera, dedescanso o de trabajo privado. A partir de estas consideraciones, la ideadel concurso queda expresada en la sección: gran parte de la edificaciónse empotra en el terreno y tan sólo emerge, se encara a la ciudad (las vis-tas hacia la misma y hacia el mar son extraordinarias) el acceso, las salasde espera y las áreas de administración, despachos y biblioteca no acce-sibles a los pacientes.

El edificio se aparta de la Ronda de Dalt y se introduce en medio un peque-ño bosque vinculado a la vegetación de Collserola, que distancia al edificiode la ciudad y lo sumerge en el ambiente natural del entorno. Se cuidaespecialmente el acceso desde la calle hasta el hall, por entender que enél se debe manifestar los objetivos del Instituto, atención, cuidado y confortpara la vista y el instrumento que la hace posible, el ojo. De ahí que alacceso, salas de espera, etc., se añada un espacio semidescubierto ysemicerrado, en cierta manera un umbráculo, que introduzca sombra ypenumbra en los espacios que dan al exterior, de igual manera que gafasoscuras, viseras o a veces la propia mano, reducen la (tantas veces moles-ta, en climas como el nuestro) excesiva intensidad de luz o de insolación.Los límites del solar se modificaron (por razones urbanísticas) durante elproceso de proyecto. Ello nos obligó a adelantar mucho el edificio en rela-ción a la Ronda de Dalt, con lo que la dimensión frontal del mismo resulta-ba excesiva. La segunda fase del proyecto, pretende reducir este impacto,relacionando el volumen del edificio con la forma del terreno, sin modificaren absoluto las ideas de principio, antes enumeradas.

41

43

ppllaannttaa ddee ccuubbiieerrttaassroof floor

0 50

m

ppllaannttaa bbaajjoo ccuubbiieerrttaassunder roof floor

45

ppllaannttaa nniivveell ddee qquuiirróóffaannoossoperating floor

ppllaannttaa nniivveell ddee bbiibblliiootteeccaalibrary floor

0 25

m

46

DOCENCIA /TEACHING

1970-891970-89

1978-811983-88

1997-99

1998-99

1999-2000

2003

2002-2003

2003-20042005

Titulación profesional como Arquitecto.Profesor de la Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Barcelona,en el Departamento de Proyectos. Profesor adjunto en la Cátedra de Proyectos II.Profesor encargado de curso en la Cátedra de Proyectos V de la EscuelaTécnica Superior de Arquitectura del Vallés. Profesor encargado de curso en la Escuela de Arquitectura Ramon Llullde Barcelona.Profesor visitante de Proyectos en la Escuela Técnica Superior deArquitectura de la Universidad de Navarra.Profesor invitado en el Département d’architecture de la EcolePolytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne.Profesor invitado como experto exterior en las comisiones de exámenesde los proyectos de final de carrera de la Ecole Polytechnique Fédéralede Lausanne.Profesor externo en la asignatura de Proyectos en la Escuela TécnicaSuperior de Arquitectura de la Universidad de Navarra.Profesor en la Escuela de Arquitectura Ramon Llull de Barcelona.Miembro del Comité Científico de la Cátedra Internacional deArquitectura de la Fundación Antonio Camuñas, 2005.

Profesor invitado en seminarios, cursos o talleres en Almería, Baeza,Barcelona, Bogotá, Graz, Lausanne, Lisboa, Málaga, Mallorca, París,Santander, Valladolid y Viena.

Professor at the Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Barcelona(Higher Technical School of Architecture of Barcelona), in the Departmentof Projects.Adjunct professor in the Department of Projects II.Professor in charge of course in the Department of Projects V at theHigher Technical School of Architecture of the Vallés.Professor in charge of course at the Escuela de Arquitectura Ramon LlullSchool of Architecture in Barcelona.Visiting professor of Projects at the Higher Technical School ofArchitecture at the Universidad de Navarra.Guest professor in the Department of Architecture at the FederalPolytechnic School of Lausanne.Guest professor acting as outside expert on exam committees for end-of-course projects at the Federal Polytechnic School of Lausanne.

Visiting professor in the fourth semester of Projects at the HigherTechnical School of Architecture at the Universidad de Navarra.Professor at the Ramon Llull School of Architecture in Barcelona.Member of the Scientific Committee in the International Faculty ofArchitecture at the Antonio Camuñas Foundation, 2005.

Guest professor at seminars, courses and workshops in Almería, Baeza,Barcelona, Bogotá, Graz, Lausanne, Lisbon, Málaga, Mallorca, Paris,Santander, Valladolid and Vienna.

PEP LLINAS

47

CONFERENCIAS /LECTURES

JURADO /JURY

EXPOSICIONES /EXHIBITIONS

1991

2003

PUBLICACIONES /PUBLICATIONS

1985

1990

1996

1999

2002

2004

1992

1998

PREMIOS /AWARDS

1977

1990

1994-95

1995

1995-96

1996

1996

1996

1997

1998

1997-98

2001

2003

2003

1995-2005

Conferencias, explicando obra propia, en Colegios y Escuelas de Arquitectura de España, Portugal, Francia, Italia, Gran Bretaña,Suiza, Alemania y Sudamérica.

Miembro del jurado en numerosos concursos de arquitectura nacionales e internacionales.

Obra seleccionada para participar en exposiciones sobre arquitectura, en diversas ciudades o centros de arquitectura nacionalese internacionales.

Comisario de la Exposición Josep Mª Jujol, organizada por el Colegio de Arquitectos de Cataluña.

Comisario de la Exposición 1% Cultural, organizada por la Generalitat de Cataluña y el Instituto Catalán del Suelo.

Obra publicada en numerosas revistas, libros nacionales e internacionales.Obra publicada en libros monográficos

Josep Llinàs, Obras y Proyectos, 1976-1985, Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de Madrid.

Documentos de Arquitectura n. 11, Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de Andalucía Oriental, delegación de Almería.

Josep Llinàs, arquitecto, editorial Tanaïs de Sevilla.

Colección Autores, Dirección General de la Vivienda, la Aquitectura y el Urbanismo, Ministerio de Fomento.

Selección de textos: Saques de esquina, editorial Pre-textos. Gerona.

Josep Llinàs. Manzana Fort Pienc. Barcelona. Editorial Caleidoscópio. Portugal.

Artículos publicados, especialmente, sobre las obras de Mies, Josep Mª Jujol, Alejandro de la Sota y José Antonio Coderch endiversas revistas nacionales e internacionales.

Autor de la monografía sobre Josep Mª Jujol, publicada por la Editorial Taschen. Alemania.

Autor de la monografía sobre el Teatro Metropol: Metropol, Teatro del Patronato Obrero, edita: Actar.

FAD de interiorismo.

Premio de Arquitectura y Urbanismo de la Villa de Madrid.

Finalista en la III Bienal de Arquitectura Española.

Ciudad de Barcelona.

Finalista en la IV Bienal de Arquitectura Española.

Rehabitec 1996.

FAD de Arquitectura.

Dragados y Construcciones de Arquitectura Española de la Fundación CEOE.

FAD de la opinión 1997.

Ciudad de Barcelona 1998.

IV Premio Manuel de la Dehesa correspondiente a la V Bienal de Arquitectura Española 1997/98.

Ciudad de Barcelona 2001.

FAD de la opinión 2003.

Ciudad de Barcelona 2003.

Premio Década 1995-2005.