Civpro Full Case 3 (COA)

-

Upload

gixx-cambri -

Category

Documents

-

view

62 -

download

19

description

Transcript of Civpro Full Case 3 (COA)

II. CAUSE OF ACTION

19Republic of the PhilippinesSUPREME COURT

Manila

SECOND DIVISION

G.R. No. 156848 October 11, 2007

PIONEER INTERNATIONAL, LTD., petitioner, vs.HON. TEOFILO GUADIZ, JR., in his capacity as Presiding Judge of Regional Trial Court, Branch 147, Makati City, and ANTONIO D. TODARO, respondents.

D E C I S I O N

CARPIO, J.:

The Case

This is a petition for review on certiorari1 of the Decision2 dated 27 September 2001 and of the Resolution3 dated 14 January 2003 of the Court of Appeals (appellate court) in CA-G.R. SP No. 54062. The Decision affirmed the Orders4 dated 4 January 19995 and 3 June 19996 of Branch 147 of the Regional Trial Court of Makati City (trial court) in Civil Case No. 98-124. The trial court denied the motion to dismiss filed by Pioneer International, Ltd. (PIL)7 in its special appearance.

The Facts

On 16 January 1998, Antonio D. Todaro (Todaro) filed a complaint for sum of money and damages with preliminary attachment against PIL, Pioneer Concrete Philippines, Inc. (PCPI), Pioneer Philippines Holdings, Inc. (PPHI), John G. McDonald (McDonald), and Philip J. Klepzig (Klepzig). PIL and its co-defendants were served copies of the summons and of the complaint at PPHI and PCPI’s office in Alabang, Muntinlupa, through Cecille L. De Leon (De Leon), who was Klepzig’s Executive Assistant.

Todaro alleged that PIL is a corporation duly organized under Australian laws, while PCPI and PPHI are corporations duly organized under Philippine laws. PIL is engaged in the ready-mix and concrete aggregates business and has established a presence worldwide. PIL established PPHI as the holding company of the stocks of its operating company in the Philippines, PCPI. McDonald is the Chief Executive Officer of PIL’s Hong Kong office while Klepzig is the President and Managing Director of PPHI and PCPI. For his part, Todaro further alleged that he was the managing director of Betonval Readyconcrete, Inc. (Betonval) from June 1975 up to his resignation in February 1996.

Before Todaro filed his complaint, there were several meetings and exchanges of letters between Todaro and the officers of Pioneer Concrete (Hong Kong) Limited, Pioneer Concrete Group HK, PPHI, and PIL. According to Todaro, PIL contacted him in May 1996 and asked if he could join it in establishing a pre-mixed concrete plant and in overseeing its operations in the Philippines. Todaro

confirmed his availability and expressed interest in joining PIL. Todaro met with several of PIL’s representatives and even gave PIL the names of three of his subordinates in Betonval whom he would like to join him in PIL.

Todaro attached nine letters, marked as Annexes "A" to "I," to his complaint. Annex "A"8 shows that on 15 July 1996, Todaro, under the letterhead of Ital Tech Distributors, Inc., sent a letter to Max Lindsay (Lindsay) of Pioneer Concrete (Hong Kong) Limited. Todaro wrote that "[m]y aim is to run again a ready-mix concrete company in the Philippines and not to be a part-time consultant. Otherwise, I could have charged your company with a much higher fee."

Annex "B"9 shows that on 4 September 1996, Lindsay, under the letterhead of Pioneer Concrete (Hong Kong) Limited, responded by fax to Todaro’s faxed letter to McDonald and proposed that Todaro "join Pioneer on a retainer basis for 2 to 3 months on the understanding that [Todaro] would become a permanent employee if as we expect, our entry proceeds." The faxed letter to McDonald referred to by Lindsay is not found in the rollo and was not attached to Todaro’s complaint.

Annex "C"10 shows that on the same date as that of Annex "B," Todaro, under the letterhead of Ital Tech Distributors, Inc., faxed another letter to Lindsay of Pioneer Concrete (Hong Kong) Limited. Todaro asked for a formal letter addressed to him about the proposed retainer. Todaro requested that the letter contain a statement on his remuneration package and on his permanent employment "with PIONEER once it has established itself on a permanent basis in the Philippines."

Annex "D"11 shows that Todaro, under the letterhead of Ital Tech Distributors, Inc., sent a letter to McDonald of PIL. Todaro confirmed the following to McDonald:

1. That I am accepting the proposal of PIONEER INT’L. as a consultant for three (3) months, starting October 1, 1996, with a retainer fee of U.S. $15,000.00 per month;

2. That after three (3) months consultancy, I should be employed by PIONEER INT’L., on a permanent basis, as its Managing Director or CEO in the Philippines. Remuneration package will be mutually agreed upon by PIONEER and the undersigned;

3. That Gino Martinel and the Sales Manager – Jun Ong, will be hired as well, on a permanent basis, by PIONEER as soon as the company is established. Salary, likewise, will be accepted by both PIONEER and the respective parties.

Annex "E"12 is a faxed letter dated 18 November 1996 of McDonald, under the letterhead of Pioneer Concrete Group HK, to Todaro of Ital Tech Distributors, Inc. The first three paragraphs of McDonald’s letter read:

Further to our recent meeting in Hong Kong, I am now able to confirm my offer to engage you as a consultant to Pioneer International Ltd. Should Pioneer proceed with an investment in the Philippines, then Pioneer would offer you a position to manage the premixed concrete operations.

Pioneer will probably be in a position to make a decision on proceeding with an investment by mid January ‘97.

The basis for your consultancy would be:

Monthly fee USD 15,000 per month billed on monthly basis and payable 15 days from billing date.

Additional pre-approved expenses to be reimbursed. Driver and secretarial support-basis for reimbursement of this to be agreed. Arrangement to commence from 1st November ‘96, reflecting your

contributions so far and to continue until Pioneer makes a decision.

Annex "F"13 shows Todaro’s faxed reply, under the letterhead of Ital Tech Distributors, Inc., to McDonald of Pioneer Concrete Group HK dated 19 November 1996. Todaro confirmed McDonald’s package concerning the consultancy and reiterated his desire to be the manager of Pioneer’s Philippine business venture.

Annex "G"14 shows Todaro’s faxed reply, under the letterhead of Ital Tech Distributors, Inc., to McDonald of PIL dated 8 April 1997. Todaro informed McDonald that he was willing to extend assistance to the Pioneer representative from Queensland. The tenor of the letter revealed that Todaro had not yet occupied his expected position.

Annex "H"15 shows Klepzig’s letter, under the letterhead of PPHI, to Todaro dated 18 September 1997. Klepzig’s message reads:

It has not proven possible for this company to meet with your expectations regarding the conditions of your providing Pioneer with consultancy services. This, and your refusal to consider my terms of offer of permanent employment, leave me no alternative but to withdraw these offers of employment with this company.

As you provided services under your previous agreement with our Pioneer Hong Kong office during the month of August, I will see that they pay you at the previous rates until the end of August. They have authorized me on behalf of Pioneer International Ltd. to formally advise you that the agreement will cease from August 31st as per our previous discussions.

Annex "I"16 shows the letter dated 20 October 1997 of K.M. Folwell (Folwell), PIL’s Executive General Manager of Australia and Asia, to Todaro. Folwell confirmed the contents of Klepzig’s 18 September 1997 letter. Folwell’s message reads:

Thank you for your letter to Dr. Schubert dated 29th September 1997 regarding the alleged breach of contract with you. Dr. Schubert has asked me to investigate this matter.

I have discussed and examined the material regarding your association with Pioneer over the period from mid 1996 through to September 1997.

Clearly your consultancy services to Pioneer Hong Kong are well documented and have been appropriately rewarded. However, in regard to your request and expectation to be given permanent employment with Pioneer Philippines Holdings, Inc. I am informed that negotiations to reach agreement on appropriate terms and conditions have not been successful.

The employment conditions you specified in your letter to John McDonald dated 11th September are well beyond our expectations.

Mr. Todaro, I regret that we do not wish to pursue our association with you any further. Mr. Klepzig was authorized to terminate this association and the letter he sent to you dated 18th September has my support.

Thank you for your involvement with Pioneer. I wish you all the best for the future. (Emphasis added)

PIL filed, by special appearance, a motion to dismiss Todaro’s complaint. PIL’s co-defendants, PCPI, PPHI, and Klepzig, filed a separate motion to dismiss.17 PIL asserted that the trial court has no jurisdiction over PIL because PIL is a foreign corporation not doing business in the Philippines. PIL also questioned the service of summons on it. Assuming arguendo that Klepzig is PIL’s agent in the Philippines, it was not Klepzig but De Leon who received the summons for PIL. PIL further stated that the National Labor Relations Commission (NLRC), and not the trial court, has jurisdiction over the subject matter of the action. It claimed that assuming that the trial court has jurisdiction over the subject matter of the action, the complaint should be dismissed on the ground of forum non-conveniens. Finally, PIL maintained that the complaint does not state a cause of action because there was no perfected contract, and no personal judgment could be rendered by the trial court against PIL because PIL is a foreign corporation not doing business in the Philippines and there was improper service of summons on PIL.

Todaro filed a Consolidated Opposition dated 26 August 1998 to refute PIL’s assertions. PIL filed, still by special appearance, a Reply on 2 October 1998.

The Ruling of the Trial Court

On 4 January 1999, the trial court issued an order18 which ruled in favor of Todaro. The trial court denied the motions to dismiss filed by PIL, PCPI, PPHI, and Klepzig.

The trial court stated that the merits of a motion to dismiss a complaint for lack of cause of action are tested on the strength of the allegation of facts in the complaint. The trial court found that the allegations in the complaint sufficiently establish a cause of action. The trial court declared that Todaro’s cause of action is based on an alleged breach of a contractual obligation and an alleged violation of Articles 19 and 21 of the Civil Code. Therefore, the cause of action does not lie within the jurisdiction of the NLRC but with the trial court.

The trial court also asserted its jurisdiction over PIL, holding that PIL did business in the Philippines when it entered into a contract with Todaro. Although PIL questions the service of summons on Klepzig, whom PIL claims is not its agent, the trial court ruled that PIL failed to adduce evidence to prove its contention. Finally, on the issue of forum non-conveniens, the trial court found that it is more convenient to hear and decide the case in the Philippines because Todaro resides in the Philippines and the contract allegedly breached involves employment in the Philippines.

PIL filed an urgent omnibus motion for the reconsideration of the trial court’s 4 January 1999 order and for the deferment of filing its answer. PCPI, PPHI, and Klepzig likewise filed an urgent omnibus motion. Todaro filed a consolidated opposition, to which PIL, PCPI, PPHI, and Klepzig filed a joint reply. The trial court issued an order19on 3 June 1999 denying the motions of PIL, PCPI, PPHI, and Klepzig. The trial court gave PIL, PCPI, PPHI, and Klepzig 15 days within which to file their respective answers.

PIL did not file an answer before the trial court and instead filed a petition for certiorari before the appellate court.

The Ruling of the Appellate Court

The appellate court denied PIL’s petition and affirmed the trial court’s ruling in toto. The dispositive portion of the appellate court’s decision reads:

WHEREFORE, premises considered, the present petition for certiorari is hereby DENIED DUE COURSE and accordingly DISMISSED. The assailed Orders dated January 4, 1999 and June 3, 1999 of the Regional Trial Court of Makati City, Branch 147, in Civil Case No, 98-124 are hereby AFFIRMED in toto.

SO ORDERED.20

On 14 January 2003, the appellate court dismissed21 PIL’s motion for reconsideration for lack of merit. The appellate court stated that PIL’s motion raised no new substantial or weighty arguments that could impel the appellate court from departing or overturning its previous decision. PIL then filed a petition for review on certiorari before this Court.

The Issues

PIL raised the following issues before this Court:

A. [The trial court] did not and cannot acquire jurisdiction over the person of [PIL] considering that:

A.1. [PIL] is a foreign corporation "not doing business" in the Philippines.

A.2. Moreover, the complaint does not contain appropriate allegations of ultimate facts showing that [PIL] is doing or transacting business in the Philippines.

A.3. Assuming arguendo that jurisdiction may be acquired over the person of [PIL], [the trial court] still failed to acquire jurisdiction since summons was improperly served on [PIL].

B. [Todaro] does not have a cause of action and the complaint fails to state a cause of action. Jurisprudence is settled in that in resolving a motion to dismiss, a court can consider all the pleadings filed in the case, including annexes, motions and all evidence on record.

C. [The trial court] did not and cannot acquire jurisdiction over the subject matter of the complaint since the allegations contained therein indubitably show that [Todaro] bases his claims on an alleged breach of an employment contract. Thus, exclusive jurisdiction is vested with the [NLRC].

D. Pursuant to the principle of forum non-conveniens, [the trial court] committed grave abuse of discretion when it took cognizance of the case.22

The Ruling of the Court

The petition has partial merit. We affirm with modification the rulings of the trial and appellate courts. Apart from the issue on service of summons, the rulings of the trial and appellate courts on the issues raised by PIL are correct.

Cause of Action

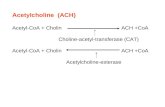

Section 2, Rule 2 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure states that a cause of action is the act or omission by which a party violates a right of another.

The general rule is that the allegations in a complaint are sufficient to constitute a cause of action against the defendants if, admitting the facts alleged, the court can render a valid judgment upon the same in accordance with the prayer therein. A cause of action exists if the following elements are present, namely: (1) a right in favor of the plaintiff by whatever means and under whatever law it arises or is created; (2) an obligation on the part of the named defendant to respect or not to violate such right; and (3) an act or omission on the part of such defendant violative of the right of the plaintiff or constituting a breach of the obligation of the defendant to the plaintiff for which the latter may maintain an action for recovery of damages.23

In the present case, the summary of Todaro’s allegations states that PIL, PCPI, PPHI, McDonald, and Klepzig did not fulfill their contractual obligation to employ Todaro on a permanent basis in PIL’s Philippine office. Todaro’s allegations are thus sufficient to establish a cause of action. We quote with approval the trial court’s ruling on this matter:

On the issue of lack of cause of action – It is well-settled that the merits of a motion to dismiss a complaint for lack of cause of action is tested on the strength of the allegations of fact contained in the complaint and no other (De Jesus, et al. vs. Belarmino, et al., 95 Phil. 366 [1954]). This Court finds that the allegations of the complaint, specifically paragraphs 13-33 thereof, paragraphs 30-33 alleging as follows:

"30. All of the acts set forth in the foregoing have been done with the knowledge, consent and/or approval of the defendants who acted in concert and/or in conspiracy with one another.

31. Under the circumstances, there is a valid contract entered into between [Todaro] and the Pioneer Group, whereby, among others, the Pioneer Group would employ [Todaro], on a permanent basis, to manage and operate the ready-mix concrete operations, if the Pioneer Group decides to invest in the Philippines.

32. The Pioneer Group has decided to invest in the Philippines. The refusal of the defendants to comply with the Pioneer Group’s undertaking to employ [Todaro] to manage their Philippine ready-mix operations, on a permanent basis, is a direct breach of an obligation under a valid and perfected contract.

33. Alternatively, assuming without conceding, that there was no contractual obligation on the part of the Pioneer Group to employ [Todaro] on a permanent basis, in their Philippine operations, the Pioneer Group and the other defendants did not act with justice, give [Todaro] his due and observe honesty and good faith and/or they have willfully caused injury to [Todaro] in a manner that is contrary to morals, good customs, and public policy, as mandated under Arts. 19 and 21 of the New Civil Code."

sufficiently establish a cause of action for breach of contract and/or violation of Articles 19 and 21 of the New Civil Code. Whether or not these allegations are true is immaterial for the court cannot inquire into the truth thereof, the test being whether, given the allegations of fact

in the complaint, a valid judgment could be rendered in accordance with the prayer in the complaint.24

It should be emphasized that the presence of a cause of action rests on the sufficiency, and not on the veracity, of the allegations in the complaint. The veracity of the allegations will have to be examined during the trial on the merits. In resolving a motion to dismiss based on lack of cause of action, the trial court is limited to the four corners of the complaint and its annexes. It is not yet necessary for the trial court to examine the truthfulness of the allegations in the complaint. Such examination is proper during the trial on the merits.

Forum Non-Conveniens

The doctrine of forum non-conveniens requires an examination of the truthfulness of the allegations in the complaint. Section 1, Rule 16 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure does not mention forum non-conveniens as a ground for filing a motion to dismiss. The propriety of dismissing a case based on forum non-conveniens requires a factual determination; hence, it is more properly considered a matter of defense. While it is within the discretion of the trial court to abstain from assuming jurisdiction on this ground, the trial court should do so only after vital facts are established to determine whether special circumstances require the court’s desistance.25

Jurisdiction over PIL

PIL questions the trial court’s exercise of jurisdiction over it on two levels. First, that PIL is a foreign corporation not doing business in the Philippines and because of this, the service of summons on PIL did not follow the mandated procedure. Second, that Todaro’s claims are based on an alleged breach of an employment contract so Todaro should have filed his complaint before the NLRC and not before the trial court.

Transacting Business in the Philippines andService of Summons

The first level has two sub-issues: PIL’s transaction of business in the Philippines and the service of summons on PIL. Section 12, Rule 14 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure provides the manner by which summons may be served upon a foreign juridical entity which has transacted business in the Philippines. Thus:

Service upon foreign private juridical entity. — When the defendant is a foreign juridical entity which has transacted business in the Philippines, service may be made on its resident agent designated in accordance with law for that purpose, or, if there be no such agent, on the government official designated by law to that effect, or any of its officers or agents within the Philippines.

As to the first sub-issue, PIL insists that its sole act of "transacting" or "doing business" in the Philippines consisted of its investment in PPHI. Under Philippine law, PIL’s mere investment in PPHI does not constitute "doing business." However, we affirm the lower courts’ ruling and declare that, based on the allegations in Todaro’s complaint, PIL was doing business in the Philippines when it negotiated Todaro’s employment with PPHI. Section 3(d) of Republic Act No. 7042, Foreign Investments Act of 1991, states:

The phrase "doing business" shall include soliciting orders, service contracts, opening offices, whether called "liaison" offices or branches; appointing representatives or distributors

domiciled in the Philippines or who in any calendar year stay in the country for a period or periods totaling one hundred eighty [180] days or more; participating in the management, supervision or control of any domestic business, firm, entity or corporation in the Philippines; and any other act or acts that imply a continuity of commercial dealings or arrangements and contemplate to that extent the performance of acts or works, or the exercise of some of the functions normally incident to, and in progressive prosecution of commercial gain or of the purpose and object of the business organization:Provided, however, That the phrase "doing business" shall not be deemed to include mere investment as a shareholder by a foreign entity in domestic corporations duly registered to do business, and/or the exercise of rights as such investor; nor having a nominee director or officer to represent its interests in such corporation; nor appointing a representative or distributor domiciled in the Philippines which transacts business in its own name and for its own account; (Emphases added)

PIL’s alleged acts in actively negotiating to employ Todaro to run its pre-mixed concrete operations in the Philippines, which acts are hypothetically admitted in PIL’s motion to dismiss, are not mere acts of a passive investor in a domestic corporation. Such are managerial and operational acts in directing and establishing commercial operations in the Philippines. The annexes that Todaro attached to his complaint give us an idea on the extent of PIL’s involvement in the negotiations regarding Todaro’s employment. In Annex "E," McDonald of Pioneer Concrete Group HK confirmed his offer to engage Todaro as a consultant of PIL. In Annex "F," Todaro accepted the consultancy. In Annex "H," Klepzig of PPHI stated that PIL authorized him to tell Todaro about the cessation of his consultancy. Finally, in Annex "I," Folwell of PIL wrote to Todaro to confirm that "Pioneer" no longer wishes to be associated with Todaro and that Klepzig is authorized to terminate this association. Folwell further referred to a Dr. Schubert and to Pioneer Hong Kong. These confirmations and references tell us that, in this instance, the various officers and companies under the Pioneer brand name do not work independently of each other. It cannot be denied that PIL had knowledge of and even authorized the non-implementation of Todaro’s alleged permanent employment. In fact, in the letters to Todaro, the word "Pioneer" was used to refer not just to PIL alone but also to all corporations negotiating with Todaro under the Pioneer name.

As further proof of the interconnection of the various Pioneer corporations with regard to their negotiations with Todaro, McDonald of Pioneer Concrete Group HK confirmed Todaro’s engagement as consultant of PIL (Annex "E") while Folwell of PIL stated that Todaro rendered consultancy services to Pioneer HK (Annex "I"). In this sense, the various Pioneer corporations were not acting as separate corporations. The behavior of the various Pioneer corporations shoots down their defense that the corporations have separate and distinct personalities, managements, and operations. The various Pioneer corporations were all working in concert to negotiate an employment contract between Todaro and PPHI, a domestic corporation.

Finally, the phrase "doing business in the Philippines" in the former version of Section 12, Rule 14 now reads "has transacted business in the Philippines." The scope is thus broader in that it is enough for the application of the Rule that the foreign private juridical entity "has transacted business in the Philippines."26

As to the second sub-issue, the purpose of summons is not only to acquire jurisdiction over the person of the defendant, but also to give notice to the defendant that an action has been commenced against it and to afford it an opportunity to be heard on the claim made against it. The requirements of the rule on summons must be strictly followed; otherwise, the trial court will not acquire jurisdiction over the defendant.

When summons is to be served on a natural person, service of summons should be made in person on the defendant.27 Substituted service is resorted to only upon the concurrence of two requisites: (1) when the defendant cannot be served personally within a reasonable time and (2) when there is impossibility of prompt service as shown by the statement in the proof of service in the efforts made to find the defendant personally and that such efforts failed.28

The statutory requirements of substituted service must be followed strictly, faithfully, and fully, and any substituted service other than by the statute is considered ineffective. Substituted service is in derogation of the usual method of service. It is a method extraordinary in character and may be used only as prescribed and in the circumstances authorized by the statute.29 The need for strict compliance with the requirements of the rule on summons is also exemplified in the exclusive enumeration of the agents of a domestic private juridical entity who are authorized to receive summons.

At present, Section 11 of Rule 14 provides that when the defendant is a domestic private juridical entity, service may be made on the "president, managing partner, general manager, corporate secretary, treasurer, or in-house counsel." The previous version of Section 11 allowed for the service of summons on the "president, manager, secretary, cashier, agent, or any of its directors." The present Section 11 qualified "manager" to "general manager" and "secretary" to "corporate secretary." The present Section 11 also removed "cashier, agent, or any of its directors" from the exclusive enumeration.

When summons is served on a foreign juridical entity, there are three prescribed ways: (1) service on its resident agent designated in accordance with law for that purpose, (2) service on the government official designated by law to receive summons if the corporation does not have a resident agent, and (3) service on any of the corporation’s officers or agents within the Philippines.30

In the present case, service of summons on PIL failed to follow any of the prescribed processes. PIL had no resident agent in the Philippines. Summons was not served on the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the designated government agency,31 since PIL is not registered with the SEC. Summons for PIL was served on De Leon, Klepzig’s Executive Assistant. Klepzig is PIL’s "agent within the Philippines" because PIL authorized Klepzig to notify Todaro of the cessation of his consultancy (Annexes "H" and "I").32 The authority given by PIL to Klepzig to notify Todaro implies that Klepzig was likewise authorized to receive Todaro’s response to PIL’s notice. Todaro responded to PIL’s notice by filing a complaint before the trial court.

However, summons was not served personally on Klepzig as agent of PIL. Instead, summons was served on De Leon, Klepzig’s Executive Assistant. In this instance, De Leon was not PIL’s agent but a mere employee of Klepzig. In effect, the sheriff33 resorted to substituted service. For symmetry, we apply the rule on substituted service of summons on a natural person and we find that no reason was given to justify the service of PIL’s summons on De Leon.

Thus, we rule that PIL transacted business in the Philippines and Klepzig was its agent within the Philippines. However, there was improper service of summons on PIL since summons was not served personally on Klepzig.

NLRC Jurisdiction

As to the second level, Todaro prays for payment of damages due him because of PIL’s non-implementation of Todaro’s alleged employment agreement with PPHI. The appellate court stated its ruling on this matter, thus:

It could not be denied that there was no existing contract yet to speak of between PIONEER INTL. and [Todaro]. Since there was an absence of an employment contract between the two parties, this Court is of the opinion and so holds that no employer-employee relationship actually exists. Record reveals that all that was agreed upon by [Todaro] and the Pioneer Concrete, acting in behalf of PIONEER INTL., was the confirmation of the offer to engage the services of the former as consultant of PIONEER INTL. (Rollo, p. 132). The failure on the part of PIONEER INTL. to abide by the said agreement, which was duly confirmed by PIONEER INTL., brought about a breach of an obligation on a valid and perfected agreement. There being no employer-employee relationship established between [PIL] and [Todaro], it could be said that the instant case falls within the jurisdiction of the regular courts of justice as the money claim of [Todaro] did not arise out of or in connection with [an] employer-employee relationship.34

Todaro’s employment in the Philippines would not be with PIL but with PPHI as stated in the 20 October 1997 letter of Folwell. Assuming the existence of the employment agreement, the employer-employee relationship would be between PPHI and Todaro, not between PIL and Todaro. PIL’s liability for the non-implementation of the alleged employment agreement is a civil dispute properly belonging to the regular courts. Todaro’s causes of action as stated in his complaint are, in addition to breach of contract, based on "violation of Articles 19 and 21 of the New Civil Code" for the "clear and evident bad faith and malice"35 on the part of defendants. The NLRC’s jurisdiction is limited to those enumerated under Article 217 of the Labor Code.36

WHEREFORE, the petition is PARTIALLY GRANTED. The Decision dated 27 September 2001 and the Resolution dated 14 January 2003 of the appellate court are AFFIRMED with the MODIFICATION that there was improper service of summons on Pioneer International, Ltd. The case is remanded to the trial court for proper service of summons and trial. No costs.

SO ORDERED.

Quisumbing, Carpio-Morales, Tinga, Velasco, Jr., JJ., concur.

19-A

Republic of the PhilippinesSUPREME COURT

Manila

THIRD DIVISION

G.R. No. 155785 April 13, 2007

SIMPLICIO GALICIA, for himself, and as Attorney-in-Fact of ROSALIA G. TORRE, PAQUITO GALICIA, NELLIE GALICIA, LETICIA G. MAESTRO and CLARO GALICIA, Petitioners, vs.LOURDES MANLIQUEZ vda. de MINDO and LILIA RICO MINANO, Respondents.

D E C I S I O N

AUSTRIA-MARTINEZ, J.:

Before the Court is a Petition for Review on Certiorari seeking to annul and set aside the Decision1 of the Court of Appeals (CA) dated January 14, 2002 in CA-G.R. SP No. 58834 and its Resolution2 of October 21, 2002 denying petitioners’ Motion for Reconsideration.

The present case originated from a complaint filed with the Regional Trial Court (RTC) of Odiongan, Romblon by herein petitioners, in their capacity as heirs of Juan Galicia (Juan), against Milagros Rico-Glori (Milagros) and her tenants Dominador Musca and Alfonso Fallar, Jr. for Recovery of Possession and Ownership, Annulment of Title, Documents and Other Papers. The case is docketed as Civil Case No. OD-306.

In their Complaint, petitioners contended that their predecessor, Juan, was the true and lawful owner of a parcel of land situated in Concepcion Sur, Sta. Maria, Romblon known as Lot No. 139 and containing an area of 5.5329 hectares, the same having been declared in his name under various tax declarations the latest of which being Tax Declaration No. 0037, Series of 1994; after years of possession of the said land, Juan was driven away from the property through force by the heirs of a certain Ines Ramirez (Ines), one of whom is defendant Milagros; because of poverty and lack of knowledge, Juan was not able to assert his right to the said property but he informed his children that they own the above-described parcel of land; and the continuous possession of the property by Milagros and her co-defendants, tenants has further deprived herein petitioners of their right over the same.

Defendants denied the allegations of petitioners in their complaint asserting that Juan was not the owner and never took possession of the disputed lot. They also contended that the subject property was part of a larger parcel of land which was acquired by Ines, Milagros’s predecessor-in-interest in 1947 from a certain Juan Galicha who is a different person from Juan Galicia.

During the scheduled pre-trial conference on May 21, 1997, none of the defendants appeared. They filed a motion for postponement of the pre-trial conference but it was belatedly received by the trial court. As a consequence, defendants were declared in default. Herein petitioners, as plaintiffs, were then allowed to present evidence ex parte.

On December 2, 1997, the RTC rendered judgment with the following dispositive portion:

WHEREFORE, premises considered, and by preponderance of evidence, judgment is hereby rendered in favor of the plaintiffs and against the defendants:

1. Declaring plaintiffs as the true and absolute owner of the property subject of the case and particularly described in paragraph II of the complaint;

2. Affirming and confirming the validity and legality of plaintiffs’ ownership over the property;

3. Ordering defendants to vacate the land adverted to in paragraph II of the complaint;

4. For the defendants to respect plaintiffs' peaceful possession and ownership of the land aforesaid; and

5. To pay the costs.

SO ORDERED.3

On December 15, 1997, the RTC received a Motion for Leave of Court to Intervene with an attached Answer-in-Intervention filed by the compulsory heirs of Ines, among whom are herein respondents, who are also co-heirs of defendant Milagros. The intervenors contended that the subject parcel of land forms part of the estate of Ines which is yet to be partitioned among them; an intestate proceeding is presently pending in the RTC of Odiongan, Romblon, Branch 81; the outcome of Civil Case No. OD-306, one way or the other, would adversely affect their interest; their rights would be better protected in the said civil case; and their intervention would not unduly delay, or in any way prejudice the rights of the original parties.

In its Order of December 23, 1997, the RTC denied the said motion to intervene on the ground that it has already rendered judgment and under Section 2, Rule 19 of the Rules of Court, the motion to intervene should have been filed before rendition of judgment by the trial court.

Meanwhile, the defendants in Civil Case No. OD-306 filed an appeal with the CA. Their Notice of Appeal was filed on February 27, 1998. On June 23, 1999, the CA issued a Resolution dismissing the appeal for failure of the defendants-appellants to file their brief within the extended period granted by the appellate court. On August 13, 1999, the abovementioned CA Resolution became final and executory.

Subsequently, the trial court issued a writ of execution dated March 3, 2000.

On May 23, 2000, herein respondents filed a petition for annulment of judgment with the CA anchored on grounds of lack of jurisdiction over their persons and property and on extrinsic fraud.

On January 14, 2002, the CA promulgated the presently assailed Decision with the following dispositive portion:

WHEREFORE, the present petition is hereby GRANTED. The Decision dated December 2, 1997 and Writ of Execution dated March 3, 2000 of Branch 82 of the Regional Trial Court of Odiongan, Romblon are hereby ANNULLED and SET ASIDE.

SO ORDERED.4

Herein petitioners filed a Motion for Reconsideration but it was denied by the CA in its Resolution5 dated October 21, 2002.

Hence, the instant petition for review based on the following assignment of errors:

1. THAT THE COURT OF APPEALS COMMITTED SERIOUS ERROR OF LAW IN ANNULLING AND SETTING ASIDE THE DECISION DATED 2 DECEMBER 1997 AND WRIT OF EXECUTION DATED 3 MARCH 2000 OF BRANCH 82 OF THE REGIONAL TRIAL COURT OF ODIONGAN, ROMBLON FOR LACK OF JURISDICTION OVER THE PERSONS OF PETITIONERS (NOW RESPONDENTS IN THE ABOVE-ENTITLED CASE), A DECISION NOT IN ACCORD WITH LAW OR WITH THE APPLICABLE DECISIONS OF THE SUPREME COURT.

2. THAT THE COURT OF APPEALS COMMITTED SERIOUS ERROR OF LAW IN NOT DISMISSING THE PETITION FOR ANNULMENT OF JUDGMENT ON THE GROUND OF ESTOPPEL ON THE PART OF THE PETITIONERS IN CA-G.R. SP. NO. 58834.6

As to their first assigned error, petitioners invoke the principle that jurisdiction over the person is acquired by the voluntary appearance of a party in court and his submission to its authority. Applying this rule in the present case, petitioners argue that by filing their Motion for Leave to Intervene in the RTC, herein respondents voluntarily submitted themselves to the authority of the trial court, hence placing themselves under its jurisdiction; that by filing the said Motion, they recognized the authority of the court to hear and decide not only their Motion but the case itself; and that by acting on their Motion, the court actually exercised jurisdiction over the persons of petitioners.

With respect to their second assigned error, petitioners contend that by respondents’ voluntary submission to the jurisdiction of the trial court they are already estopped in denying the authority of the court which they invoked when they filed their Motion. Petitioners also contend that respondents had several opportunities to raise the issue of the court’s lack of jurisdiction over their persons but they remained silent and did not pursue the remedies available to them for an unreasonable length of time; hence, they are now barred by laches from questioning the court’s jurisdiction.

On the other hand, respondents counter that the CA did not err in setting aside the trial court's decision on the ground that defendants, as indispensable parties, were not joined in the complaint. Respondents argue that the CA correctly held that when an indispensable party is not before the court then the action should be dismissed because the absence of such indispensable party renders all subsequent actions of the court null and void for want of authority to act not only as against him but even as against those present.

Respondents also aver that even assuming that herein petitioners were the true owners of the subject land, they have lost such ownership by extinctive prescription because respondents and their predecessors had been in uninterrupted adverse possession of the subject lot for more than 40 years. As such, they had become the owners thereof by acquisitive prescription.

The petition lacks merit but the CA Decision will have to be modified in the interest of substantial justice and for the orderly administration of justice, as will be shown forthwith.

It is true that the allowance and disallowance of a motion to intervene is addressed to the sound discretion of the court hearing the case.7 However, jurisprudence is replete with cases wherein the Court ruled that a motion to intervene may be entertained or allowed even if filed after judgment was rendered by the trial court, especially in cases where the intervenors are indispensable parties.8 In Pinlac v. Court of Appeals, this Court held:

The rule on intervention, like all other rules of procedure, is intended to make the powers of the Court fully and completely available for justice. It is aimed to facilitate a comprehensive adjudication of rival claims overriding technicalities on the timeliness of the filing thereof. Indeed, in exceptional cases, the Court has allowed intervention notwithstanding the rendition of judgment by the trial court.9

Since it is not disputed that herein respondents are compulsory heirs of Ines who stand to be affected by the judgment of the trial court, the latter should have granted their Motion to Intervene and should have admitted their Answer-in-Intervention.

Section 7, Rule 3 of the Rules of Court, defines indispensable parties as parties-in-interest without whom there can be no final determination of an action. As such, they must be joined either as plaintiffs or as defendants. The general rule with reference to the making of parties in a civil action requires the joinder of all necessary parties where possible and the joinder of all indispensable parties under any and all conditions, their presence being a sine qua non for the exercise of judicial power.10 It is precisely when an indispensable party is not before the court that the action

should be dismissed.11 The absence of an indispensable party renders all subsequent actions of the court null and void for want of authority to act, not only as to the absent parties but even as to those present.12 The evident aim and intent of the Rules regarding the joinder of indispensable and necessary parties is a complete determination of all possible issues, not only between the parties themselves but also as regards to other persons who may be affected by the judgment.13 A valid judgment cannot even be rendered where there is want of indispensable parties.14

1^wphi1.net

As to the question of whether the trial court acquired jurisdiction over the persons of herein respondents, the Court has held that the filing of motions seeking affirmative relief, such as, to admit answer, for additional time to file answer, for reconsideration of a default judgment, and to lift order of default with motion for reconsideration, are considered voluntary submission to the jurisdiction of the court.15 Hence, in the present case, when respondents filed their Motion for Leave to Intervene, attaching thereto their Answer-in-Intervention, they have effectively submitted themselves to the jurisdiction of the court and the court, in turn, acquired jurisdiction over their persons. But this circumstance did not cure the fatal defect of non-inclusion of respondents as indispensable parties in the complaint filed by petitioner. It must be emphasized that respondents were not able to participate during the pre-trial much less present evidence in support of their claims. In other words, the court acquired jurisdiction over the persons of herein respondents only when they filed their Motion for Leave to Intervene with the RTC. Prior to that, they were strangers to Civil Case No. OD-306.

It is basic that no man shall be affected by any proceeding to which he is a stranger, and strangers to a case are not bound by judgment rendered by the court.16 In the present case, respondents and their co-heirs are adversely affected by the judgment rendered by the trial court considering their ostensible ownership of the property. It will be the height of inequity to declare herein petitioners as owners of the disputed lot without giving respondents the opportunity to present any evidence in support of their claim that the subject property still forms part of the estate of their deceased predecessor and is the subject of a pending action for partition among the compulsory heirs. Much more, it is tantamount to a violation of the constitutional guarantee that no person shall be deprived of property without due process of law.17

1ªvvphi1.nét

This Court held in Metropolitan Bank and Trust Company v. Alejo that:

A void judgment for want of jurisdiction is no judgment at all. It cannot be the source of any right nor the creator of any obligation. All acts performed pursuant to it and all claims emanating from it have no legal effect. Hence, it can never become final and any writ of execution based on it is void: x x x it may be said to be a lawless thing which can be treated as an outlaw and slain at sight, or ignored wherever and whenever it exhibits its head.18

In the absence of herein respondents and their co-heirs who are indispensable parties, the trial court had in the first place no authority to act on the case. Thus, the judgment of the trial court was null and void due to lack of jurisdiction over indispensable parties.19 The CA correctly annulled the RTC Decision and writ of execution.

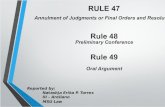

As to the timeliness of the petition for annulment of judgment filed with the CA, Section 3, Rule 47 of the Rules of Court provides that a petition for annulment of judgment based on extrinsic fraud must be filed within four years from its discovery; and if based on lack of jurisdiction, before it is barred by laches or estoppel.

The principle of laches or "stale demands" ordains that the failure or neglect, for an unreasonable and unexplained length of time, to do that which by exercising due diligence could or should have

been done earlier, or the negligence or omission to assert a right within a reasonable time, warrants a presumption that the party entitled to assert it either has abandoned it or declined to assert it.20

There is no absolute rule as to what constitutes laches or staleness of demand; each case is to be determined according to its particular circumstances.21 The question of laches is addressed to the sound discretion of the court and, being an equitable doctrine, its application is controlled by equitable considerations.22 It cannot be used to defeat justice or perpetrate fraud and injustice.23 It is the better rule that courts, under the principle of equity, will not be guided or bound strictly by the statute of limitations or the doctrine of laches when to do so, manifest wrong or injustice would result.24

In the present case, the CA found no evidence to show when respondents acquired knowledge of the complaint that petitioners filed with the RTC. Moreover, the Court finds that herein respondents' right to due process is the overriding consideration in allowing them to intervene in Civil Case No. OD-306.

Petitioners also fault herein respondents for their failure to avail of other remedies before filing a petition for annulment of judgment with the CA. Petitioners cited the remedies enumerated by the RTC in its Order of December 23, 1997. However, the Court notes that the remedies enumerated therein refer to those available to a party who has been declared in default. In the present case, herein respondents could not have been declared in default, and thus could not have availed of these remedies, because they never became parties to Civil Case No. OD-306.

The settled rule is that a judgment rendered or final order issued by the RTC without jurisdiction is null and void and may be assailed any time either collaterally or in a direct action or by resisting such judgment or final order in any action or proceeding whenever it is invoked, unless barred by laches.25 Indeed, jurisprudence upholds the soundness of an independent action to declare as null and void a judgment rendered without jurisdiction as in this case.26

As a result of and in consonance with the foregoing discussions, the complaint filed by herein petitioners with the trial court should have been dismissed at the outset, in the absence of indispensable parties.

Inevitably, the following questions come to mind: what happens to the original defendants who were declared as in default and judgment by default was rendered against them? What happens to the final and executory dismissal of the appeal of the defaulted defendants by the CA?

It is an accepted rule of procedure for this Court to strive to settle the entire controversy in a single proceeding, leaving no root or branch to bear the seeds of future litigation.27

In concurrence therewith, the Court makes the following observations:

To dismiss the complaint of herein petitioners for non-inclusion of herein respondents as indispensable parties, the former would have no other recourse but to file anew a complaint against the latter and the original defendants. This would not be in keeping with the Court's policy of promoting a just and inexpensive disposition of a case. It is best that the complaint remains which is deemed amended by the admission of the Answer-in-Intervention of the indispensable parties.

The trial court’s declaration of the defendants as in default in Civil Case No. OD-306 for their failure to attend the pre-trial conference and the consequent final and executory judgment by default, are altogether void and of no effect considering that the RTC acted without jurisdiction from the very

beginning because of non-inclusion of indispensable parties. The Court reiterates the ruling in Metropolitan Bank and Trust Company that void judgment for want of jurisdiction is no judgment at all; it cannot be the source of any right nor the creator of any obligation.28

Parties are reverted back to the stage where all the defendants have filed their respective Answers.

WHEREFORE, the petition is DENIED. The assailed Decision and Resolution of the Court of Appeals areAFFIRMED with MODIFICATION to the effect that the Regional Trial Court of Odiongan, Romblon, Branch 82 is ordered to GRANT the Motion for Leave to Intervene of respondents and their other co-heirs, ADMIT their Answer-in-Intervention, MAINTAIN the Answer of original defendants, and from there to PROCEED with Civil Case No. OD-306 in accordance with the Rules of Court.

Costs against petitioners.

SO ORDERED.

MA. ALICIA AUSTRIA-MARTINEZAssociate Justice

WE CONCUR:

CONSUELO YNARES-SANTIAGOAssociate Justice

Chairperson

ROMEO J. CALLEJO, SR.Associate Justice

MINITA V. CHICO-NAZARIOAsscociate Justice

ANTONIO EDUARDO B. NACHURAAssociate Justice

A T T E S T A T I O N

I attest that the conclusions in the above Decision had been reached in consultation before the case was assigned to the writer of the opinion of the Court’s Division.

CONSUELO YNARES-SANTIAGOAssociate JusticeChairperson, Third Division

C E R T I F I C A T I O N

Pursuant to Section 13, Article VIII of the Constitution, and the Division Chairperson’s attestation, it is hereby certified that the conclusions in the above Decision had been reached in consultation before the case was assigned to the writer of the opinion of the Court’s Division.

REYNATO S. PUNOChief Justice

III. Parties to civil action

20.

THIRD DIVISION

[G.R. No. 162788. July 28, 2005]

Spouses JULITA DE LA CRUZ and FELIPE DE LA CRUZ, petitioners, vs. PEDRO JOAQUIN, respondent.

D E C I S I O NPANGANIBAN, J.:

The Rules require the legal representatives of a dead litigant to be substituted as parties to a litigation. This requirement is necessitated by due process. Thus, when the rights of the legal representatives of a decedent are actually recognized and protected, noncompliance or belated formal compliance with the Rules cannot affect the validity of the promulgated decision. After all, due process had thereby been satisfied.

The Case

Before us is a Petition for Review[1] under Rule 45 of the Rules of Court, assailing the August 26, 2003 Decision[2] and the March 9, 2004 Resolution[3] of the Court of Appeals (CA) in CA-GR CV No. 34702. The challenged Decision disposed as follows:

“WHEREFORE, the foregoing considered, the appeal is DISMISSED and the assailed decision accordingly AFFIRMED in toto. No costs.”[4]

On the other hand, the trial court’s affirmed Decision disposed as follows:

“WHEREFORE, judgment is hereby rendered:

“a) declaring the Deed of Absolute Sale (Exh. ‘D’) and ‘Kasunduan’ (Exhibit B), to be a sale with right of repurchase;

“b) ordering the plaintiff to pay the defendants the sum of P9,000.00 by way of repurchasing the land in question;

“c) ordering the defendants to execute a deed of reconveyance of said land in favor of the plaintiff after the latter has paid them the amount of P9,000.00 to repurchase the land in question;

“d) ordering the defendants to yield possession of the subject land to the plaintiff after the latter has paid them the amount of P9,000.00 to repurchase the property from them; and

“e) ordering the defendants to pay the plaintiff the amount of P10,000.00 as actual and compensatory damages; the amount of P5,000[.00] as exemplary damages; the amount of P5,000.00 as expenses of litigation and the amount of P5,000.00 by way of attorney’s fees.”[5]

The Facts

The case originated from a Complaint for the recovery of possession and ownership, the cancellation of title, and damages, filed by Pedro Joaquin against petitioners in the Regional Trial Court of Baloc, Sto. Domingo, Nueva Ecija. [6] Respondent alleged that he had obtained a loan from them in the amount of P9,000 on June 29, 1974, payable after five (5) years; that is, on June 29, 1979. To secure the payment of the obligation, he supposedly executed a Deed of Sale in favor of petitioners. The Deed was for a parcel of land in Pinagpanaan, Talavera, Nueva Ecija, covered by TCT No. T-111802. The parties also executed another document entitled “Kasunduan.” [7]

Respondent claimed that the Kasunduan showed the Deed of Sale to be actually an equitable mortgage.[8] Spouses De la Cruz contended that this document was merely an accommodation to allow the repurchase of the property until June 29, 1979, a right that he failed to exercise.[9]

On April 23, 1990, the RTC issued a Decision in his favor. The trial court declared that the parties had entered into a sale with a right of repurchase. [10] It further held that respondent had made a valid tender of payment on two separate occasions to exercise his right of repurchase.[11] Accordingly, petitioners were required to reconvey the property upon his payment.[12]

Ruling of the Court of Appeals

Sustaining the trial court, the CA noted that petitioners had given respondent the right to repurchase the property within five (5) years from the date of the sale or until June 29, 1979. Accordingly, the parties executed the Kasunduan to express the terms and conditions of their actual agreement. [13] The appellate court also found no reason to

overturn the finding that respondent had validly exercised his right to repurchase the land.[14]

In the March 9, 2004 Resolution, the CA denied reconsideration and ordered a substitution by legal representatives, in view of respondent’s death on December 24, 1988.[15]

Hence, this Petition.[16]

The Issues

Petitioners assign the following errors for our consideration:

“I. Public Respondent Twelfth Division of the Honorable Court of Appeals seriously erred in dismissing the appeal and affirming in toto the Decision of the trial court in Civil Case No. SD-838;

“II. Public Respondent Twelfth Division of the Honorable Court of Appeals likewise erred in denying [petitioners’] Motion for Reconsideration given the facts and the law therein presented.”[17]

Succinctly, the issues are whether the trial court lost jurisdiction over the case upon the death of Pedro Joaquin, and whether respondent was guilty of forum shopping. [18]

The Court’s Ruling

The Petition has no merit.

First Issue:Jurisdiction

Petitioners assert that the RTC’s Decision was invalid for lack of jurisdiction. [19] They claim that respondent died during the pendency of the case. There being no substitution by the heirs, the trial court allegedly lacked jurisdiction over the litigation. [20]

Rule on Substitution

When a party to a pending action dies and the claim is not extinguished, [21] the Rules of Court require a substitution of the deceased. The procedure is specifically governed by Section 16 of Rule 3, which reads thus:

“Section 16. Death of a party; duty of counsel. –Whenever a party to a pending action dies, and the claim is not thereby extinguished, it shall be the duty of his counsel to inform the court within thirty (30) days after such death of the fact thereof, and to give the name and address of his legal representative or representatives. Failure of counsel to comply with this duty shall be a ground for disciplinary action.

“The heirs of the deceased may be allowed to be substituted for the deceased, without requiring the appointment of an executor or administrator and the court may appoint a guardian ad litem for the minor heirs.

“The court shall forthwith order said legal representative or representatives to appear and be substituted within a period of thirty (30) days from notice.

“If no legal representative is named by the counsel for the deceased party, or if the one so named shall fail to appear within the specified period, the court may order the opposing party, within a specified time, to procure the appointment of an executor or administrator for the estate of the deceased, and the latter shall immediately appear for and on behalf of the deceased. The court charges in procuring such appointment, if defrayed by the opposing party, may be recovered as costs.”

The rule on the substitution of parties was crafted to protect every party’s right to due process.[22] The estate of the deceased party will continue to be properly represented in the suit through the duly appointed legal representative. [23] Moreover, no adjudication can be made against the successor of the deceased if the fundamental right to a day in court is denied.[24]

The Court has nullified not only trial proceedings conducted without the appearance of the legal representatives of the deceased, but also the resulting judgments. [25] In those instances, the courts acquired no jurisdiction over the persons of the legal representatives or the heirs upon whom no judgment was binding. [26]

This general rule notwithstanding, a formal substitution by heirs is not necessary when they themselves voluntarily appear, participate in the case, and present evidence in defense of the deceased.[27] These actions negate any claim that the right to due process was violated.

The Court is not unaware of Chittick v. Court of Appeals,[28] in which the failure of the heirs to substitute for the original plaintiff upon her death led to the nullification of the trial court’s Decision. The latter had sought to recover support in arrears and her share in the conjugal partnership. The children who allegedly substituted for her refused to continue the case against their father and vehemently objected to their inclusion as parties.[29] Moreover, because he died during the pendency of the case, they were bound to substitute for the defendant also. The substitution effectively merged the persons of the plaintiff and the defendant and thus extinguished the obligation being sued upon.[30]

Clearly, the present case is not similar, much less identical, to the factual milieu of Chittick.

Strictly speaking, the rule on the substitution by heirs is not a matter of jurisdiction, but a requirement of due process. Thus, when due process is not violated, as when the right of the representative or heir is recognized and protected, noncompliance or belated formal compliance with the Rules cannot affect the validity of a promulgated decision.[31] Mere failure to substitute for a deceased plaintiff is not a sufficient ground to nullify a trial court’s decision. The alleging party must prove that there was an undeniable violation of due process.

Substitution inthe Instant Case

The records of the present case contain a “Motion for Substitution of Party Plaintiff” dated February 15, 2002, filed before the CA. The prayer states as follows:

“WHEREFORE, it is respectfully prayed that the Heirs of the deceased plaintiff-appellee as represented by his daughter Lourdes dela Cruz be substituted as party-plaintiff for the said Pedro Joaquin.

“It is further prayed that henceforth the undersigned counsel [32] for the heirs of Pedro Joaquin be furnished with copies of notices, orders, resolutions and other pleadings at its address below.”

Evidently, the heirs of Pedro Joaquin voluntary appeared and participated in the case. We stress that the appellate court had ordered[33] his legal representatives to appear and substitute for him. The substitution even on appeal had been ordered correctly. In all proceedings, the legal representatives must appear to protect the interests of the deceased.[34] After the rendition of judgment, further proceedings may be held, such as a motion for reconsideration or a new trial, an appeal, or an execution. [35]

Considering the foregoing circumstances, the Motion for Substitution may be deemed to have been granted; and the heirs, to have substituted for the deceased, Pedro Joaquin. There being no violation of due process, the issue of substitution cannot be upheld as a ground to nullify the trial court’s Decision.

Second Issue:Forum Shopping

Petitioners also claim that respondents were guilty of forum shopping, a fact that should have compelled the trial court to dismiss the Complaint. [36] They claim that prior to the commencement of the present suit on July 7, 1981, respondent had filed a civil

case against petitioners on June 25, 1979. Docketed as Civil Case No. SD-742 for the recovery of possession and for damages, it was allegedly dismissed by the Court of First Instance of Nueva Ecija for lack of interest to prosecute.

Forum Shopping Defined

Forum shopping is the institution of two or more actions or proceedings involving the same parties for the same cause of action, either simultaneously or successively, on the supposition that one or the other court would make a favorable disposition. [37] Forum shopping may be resorted to by a party against whom an adverse judgment or order has been issued in one forum, in an attempt to seek a favorable opinion in another, other than by an appeal or a special civil action for certiorari.[38]

Forum shopping trifles with the courts, abuses their processes, degrades the administration of justice, and congests court dockets.[39] Willful and deliberate violation of the rule against it is a ground for the summary dismissal of the case; it may also constitute direct contempt of court.[40]

The test for determining the existence of forum shopping is whether the elements of litis pendentia are present, or whether a final judgment in one case amounts to res judicata in another.[41] We note, however, petitioners’ claim that the subject matter of the present case has already been litigated and decided. Therefore, the applicable doctrine is res judicata.[42]

Applicability of Res Judicata

Under res judicata, a final judgment or decree on the merits by a court of competent jurisdiction is conclusive of the rights of the parties or their privies, in all later suits and on all points and matters determined in the previous suit. [43] The term literally means a “matter adjudged, judicially acted upon, or settled by judgment.” [44] The principle bars a subsequent suit involving the same parties, subject matter, and cause of action. Public policy requires that controversies must be settled with finality at a given point in time.

The elements of res judicata are as follows: (1) the former judgment or order must be final; (2) it must have been rendered on the merits of the controversy; (3) the court that rendered it must have had jurisdiction over the subject matter and the parties; and (4) there must have been -- between the first and the second actions -- an identity of parties, subject matter and cause of action.[45]

Failure to Support Allegation

The onus of proving allegations rests upon the party raising them. [46] As to the matter of forum shopping and res judicata, petitioners have failed to provide this Court

with relevant and clear specifications that would show the presence of an identity of parties, subject matter, and cause of action between the present and the earlier suits. They have also failed to show whether the other case was decided on the merits. Instead, they have made only bare assertions involving its existence without reference to its facts. In other words, they have alleged conclusions of law without stating any factual or legal basis. Mere mention of other civil cases without showing the identity of rights asserted and reliefs sought is not enough basis to claim that respondent is guilty of forum shopping, or that res judicata exists.[47]

WHEREFORE, the Petition is DENIED and the assailed Decision and Resolution are AFFIRMED. Costs against petitioners.

SO ORDERED.Sandoval-Gutierrez, Corona, Carpio-Morales, and Garcia, JJ., concur.

20-A

Republic of the PhilippinesSUPREME COURT

Manila

EN BANC

G.R. No. 110318 August 28, 1996

COLUMBIA PICTURES, INC., ORION PICTURES CORPORATION, PARAMOUNT PICTURES CORPORATION, TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX FILM CORPORATION, UNITED ARTISTS CORPORATION, UNIVERSAL CITY STUDIOS, INC., THE WALT DISNEY COMPANY, and WARNER BROTHERS, INC., petitioners, vs.COURT OF APPEALS, SUNSHINE HOME VIDEO, INC. and DANILO A. PELINDARIO, respondents.

REGALADO, J.:p

Before us is a petition for review on certiorari of the decision of the Court of Appeals 1 promulgated on July 22, 1992 and its resolution 2 of May 10, 1993 denying petitioners' motion for reconsideration, both of which sustained the order 3 of the Regional Trial Court, Branch 133, Makati, Metro Manila, dated November 22, 1988 for the quashal of Search Warrant No. 87-053 earlier issued per its own order 4 on September 5, 1988 for violation of Section 56 of Presidential Decree No. 49, as amended, otherwise known as the "Decree on the Protection of Intellectual Property."

The material facts found by respondent appellate court are as follows:

Complainants thru counsel lodged a formal complaint with the National Bureau of Investigation for violation of PD No. 49, as amended, and sought its assistance in their anti-film piracy drive. Agents of the NBI and private researchers made discreet surveillance on various video establishments in Metro Manila including Sunshine Home Video Inc. (Sunshine for brevity), owned and operated by Danilo A. Pelindario with address at No. 6 Mayfair Center, Magallanes, Makati, Metro Manila.

On November 14, 1987, NBI Senior Agent Lauro C. Reyes applied for a search warrant with the courta quo against Sunshine seeking the seizure, among others, of pirated video tapes of copyrighted films all of which were enumerated in a list attached to the application; and, television sets, video cassettes and/or laser disc recordings equipment and other machines and paraphernalia used or intended to be used in the unlawful exhibition, showing, reproduction, sale, lease or disposition of videograms tapes in the premises above described. In the hearing of the application, NBI Senior Agent Lauro C. Reyes, upon questions by the court a quo, reiterated in substance his averments in his affidavit. His testimony was corroborated by another witness, Mr. Rene C. Baltazar. Atty. Rico V. Domingo's deposition was also taken. On the basis of the affidavits and depositions of NBI Senior Agent Lauro C. Reyes, Rene C. Baltazar and Atty. Rico V. Domingo, Search Warrant No. 87-053 for violation of Section 56 of PD No. 49, as amended, was issued by the court a quo.

The search warrant was served at about 1:45 p.m. on December 14, 1987 to Sunshine and/or their representatives. In the course of the search of the premises indicated in the search warrant, the NBI Agents found and seized various video tapes of duly copyrighted motion pictures/films owned or exclusively distributed by private complainants, and machines, equipment, television sets, paraphernalia, materials, accessories all of which were included in the receipt for properties accomplished by the raiding team. Copy of the receipt was furnished and/or tendered to Mr. Danilo A. Pelindario, registered owner-proprietor of Sunshine Home Video.

On December 16, 1987, a "Return of Search Warrant" was filed with the Court.

A "Motion To Lift the Order of Search Warrant" was filed but was later denied for lack of merit (p. 280, Records).

A Motion for reconsideration of the Order of denial was filed. The court a quo granted the said motion for reconsideration and justified it in this manner:

It is undisputed that the master tapes of the copyrighted films from which the pirated films were allegedly copies (sic), were never presented in the proceedings for the issuance of the search warrants in question. The orders of the Court granting the search warrants and denying the urgent motion to lift order of search warrants were, therefore, issued in error. Consequently, they must be set aside. (p. 13, Appellant's Brief) 5

Petitioners thereafter appealed the order of the trial court granting private respondents' motion for reconsideration, thus lifting the search warrant which it had theretofore issued, to the Court of Appeals. As stated at the outset, said appeal was dismissed and the motion for reconsideration thereof was denied. Hence, this petition was brought to this Court particularly

challenging the validity of respondent court's retroactive application of the ruling in 20th Century Fox Film Corporation vs. Court of Appeals, et al., 6 in dismissing petitioners' appeal and upholding the quashal of the search warrant by the trial court.

I

Inceptively, we shall settle the procedural considerations on the matter of and the challenge to petitioners' legal standing in our courts, they being foreign corporations not licensed to do business in the Philippines.

Private respondents aver that being foreign corporations, petitioners should have such license to be able to maintain an action in Philippine courts. In so challenging petitioners' personality to sue, private respondents point to the fact that petitioners are the copyright owners or owners of exclusive rights of distribution in the Philippines of copyrighted motion pictures or films, and also to the appointment of Atty. Rico V. Domingo as their attorney-in-fact, as being constitutive of "doing business in the Philippines" under Section 1 (f)(1) and (2), Rule 1 of the Rules of the Board of Investments. As foreign corporations doing business in the Philippines, Section 133 of Batas Pambansa Blg. 68, or the Corporation Code of the Philippines, denies them the right to maintain a suit in Philippine courts in the absence of a license to do business. Consequently, they have no right to ask for the issuance of a search warrant. 7

In refutation, petitioners flatly deny that they are doing business in the Philippines, 8 and contend that private respondents have not adduced evidence to prove that petitioners are doing such business here, as would require them to be licensed by the Securities and Exchange Commission, other than averments in the quoted portions of petitioners' "Opposition to Urgent Motion to Lift Order of Search Warrant" dated April 28, 1988 and Atty. Rico V. Domingo's affidavit of December 14, 1987. Moreover, an exclusive right to distribute a product or the ownership of such exclusive right does not conclusively prove the act of doing business nor establish the presumption of doing business.9

The Corporation Code provides:

Sec. 133. Doing business without a license. — No foreign corporation transacting business in the Philippines without a license, or its successors or assigns, shall be permitted to maintain or intervene in any action, suit or proceeding in any court or administrative agency of the Philippines; but such corporation may be sued or proceeded against before Philippine courts or administrative tribunals on any valid cause of action recognized under Philippine laws.

The obtainment of a license prescribed by Section 125 of the Corporation Code is not a condition precedent to the maintenance of any kind of action in Philippine courts by a foreign corporation. However, under the aforequoted provision, no foreign corporation shall be permitted to transact business in the Philippines, as this phrase is understood under the Corporation Code, unless it shall have the license required by law, and until it complies with the law intransacting business here, it shall not be permitted to maintain any suit in local courts. 10 As thus interpreted, any foreign corporation not doing business in the Philippines may maintain an action in our courts upon any cause of action, provided that the subject matter and the defendant are within the jurisdiction of the court. It is not the absence of the prescribed license but "doing business" in the Philippines without such license which debars the foreign corporation from access to our courts. In other words, although a foreign corporation is without license to transact business in the Philippines, it does not follow that it has no capacity to bring an action. Such license is not necessary if it is not engaged in business in the Philippines. 11

Statutory provisions in many jurisdictions are determinative of what constitutes "doing business" or "transacting business" within that forum, in which case said provisions are controlling there. In others where no such definition or qualification is laid down regarding acts or transactions failing within its purview, the question rests primarily on facts and intent. It is thus held that all the combined acts of a foreign corporation in the State must be considered, and every circumstance is material which indicates a purpose on the part of the corporation to engage in some part of its regular business in the State. 12

No general rule or governing principles can be laid down as to what constitutes "doing" or "engaging in" or "transacting" business. Each case must be judged in the light of its own peculiar environmental circumstances. 13 The true tests, however, seem to be whether the foreign corporation is continuing the body or substance of the business or enterprise for which it was organized or whether it has substantially retired from it and turned it over to another. 14

As a general proposition upon which many authorities agree in principle, subject to such modifications as may be necessary in view of the particular issue or of the terms of the statute involved, it is recognized that a foreign corporation is "doing," "transacting," "engaging in," or "carrying on" business in the State when, and ordinarily only when, it has entered the State by its agents and is there engaged in carrying on and transacting through them some substantial part of its ordinary or customary business, usually continuous in the sense that it may be distinguished from merely casual, sporadic, or occasional transactions and isolated acts. 15

The Corporation Code does not itself define or categorize what acts constitute doing or transacting business in the Philippines. Jurisprudence has, however, held that the term implies a continuity of commercial dealings and arrangements, and contemplates, to that extent, the performance of acts or works or the exercise of some of the functions normally incident to or in progressive prosecution of the purpose and subject of its organization. 16

This traditional case law definition has evolved into a statutory definition, having been adopted with some qualifications in various pieces of legislation in our jurisdiction.

For instance, Republic Act No. 5455 17 provides:

Sec. 1. Definitions and scope of this Act. — (1) . . . ; and the phrase "doing business" shall include soliciting orders, purchases, service contracts, opening offices, whether called "liaison" offices or branches; appointing representatives or distributors who are domiciled in the Philippines or who in any calendar year stay in the Philippines for a period or periods totalling one hundred eighty days or more; participating in the management, supervision or control of any domestic business firm, entity or corporation in the Philippines; and any other act or acts that imply a continuity of commercial dealings or arrangements, and contemplate to that extent the performance of acts or works, or the exercise of some of the functions normally incident to, and in progressive prosecution of, commercial gain or of the purpose and object of the business organization.

Presidential Decree No. 1789, 18 in Article 65 thereof, defines "doing business" to include soliciting orders, purchases, service contracts, opening offices, whether called "liaison" offices or branches; appointing representatives or distributors who are domiciled in the Philippines or who in any calendar year stay in the Philippines for a period or periods totalling one hundred eighty days or more; participating in the management, supervision or control of any domestic business firm, entity or corporation in the Philippines, and any other act or acts that imply a continuity of

commercial dealings or arrangements and contemplate to that extent the performance of acts or works, or the exercise of some of the functions normally incident to, and in progressive prosecution of, commercial gain or of the purpose and object of the business organization.

The implementing rules and regulations of said presidential decree conclude the enumeration of acts constituting "doing business" with a catch-all definition, thus:

Sec. 1(g). "Doing Business" shall be any act or combination of acts enumerated in Article 65 of the Code. In particular "doing business" includes:

xxx xxx xxx

(10) Any other act or acts which imply a continuity of commercial dealings or arrangements, and contemplate to that extent the performance of acts or works, or the exercise of some of the functions normally incident to, or in the progressive prosecution of, commercial gain or of the purpose and object of the business organization.

Finally, Republic Act No. 7042 19 embodies such concept in this wise:

Sec. 3. Definitions. — As used in this Act:

xxx xxx xxx